by Sandro Mezzadra, translated by Leeds Plan C — Italian | French

As part of their Autumn women’s collection, H&M has recently launched an outfit clearly modeled on the uniforms worn by Kurdish female fighters, whose images have been disseminated by media around the world. More or less at the same time, close to the Syrian border, Turkish security forces attacked Kurds who were expressing their solidarity with Kobanê, the city that has been resisting for weeks the siege launched by the Islamic State (IS). Those borders, which were so porous to the jihadist militants over the last months, are now hermetically sealed to the PKK fighters rushing to join Kobanê. The Kurdish-Syrian city faces the ISIS siege alone – only defended by a handful of men and women, members of the Kurdish People’s Defence Units (YPG), armed with Kalashnikovs against IS’ tanks and heavy weapons. Interventions by the ‘anti-terrorist coalition’, led by the United States, have been so far sporadic and absolutely useless. And some black flags are already waving in Kobanê.

But who are those men and women, the YPG/YPJ fighters? Western media frequently call them ‘Peshmerga’, a term whose ‘exoticism’ obviously pleases them. Unfortunately, ‘Peshmergas’ are only the militias of KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party), the party led by Masoud Barzani, President of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq. And the truth is that these militias abandoned their positions near Sinjar in early August, leaving IS full scope and putting at risk the lives of thousands of Yazidis and other religious minorities. It has been the fighting units of the PKK and the YPG who have taken the area and faced IS with great strength, continuing the battle that they have been fighting for months against the fascist Islamic State.

Yes, it is true that IS has been ‘created’ and favoured by emirates, petro-monarchies, Turks and Americans; but in the end it is nothing but Fascism. We were reminded of it last week by the 19-year-old Ceylan Ozalp, who used her last bullet to kill herself in Kobanê and avoid falling in the hands of her IS persecutors. Some have called her a kamikaze, but who could fail to see the link between that bullet (that supreme gesture of freedom) and the cyanide pill kept in the pocket by several generations of partisans and fighters against fascism and colonialism, from Italy to Algeria and Argentina?

And how could we overlook the reasons why IS has focused their forces on Kobanê? The city is the centre to one of the three regions —the other two being Afrin and Jazira— which have constituted themselves as ‘democratic autonomous regions’ for a confederation of ‘Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians and Chechens’, as stated in the preamble to the extraordinary Charter of Rojava (as Western/Syrian Kurdistan is called). This is a text that speaks of freedom, justice, dignity and democracy; of equality and ‘environmental sustainability’. In Rojava feminism is not only embodied in the female fighters, but also in the principle of equal participation at every organ of self-government, which questions patriarchy on a daily basis. And this self-government, in spite of multiple contradictions and under extremely hard conditions, expresses a real commitment to cooperation between equal and free people. Even more: being coherent with the anti-nationalistic turn within Öcalan’s PKK, with which the YPG/YPJ are linked, there is a clear rejection not only of any kind of ethnic absolutism or religious fundamentalism, but also of any nationalistic derive of the Kurdish people’s struggle. And this is happening in the Middle East of today, where people slaughter or are slaughtered on religious or ethnic grounds.

It suffices to listen to the male and female fighters of the YPG/YPJ, whose words are easy to find online, to understand that these girls and boys, these men and women have taken up arms to affirm and defend this way of living and cooperating. It is thus easy to understand the reasons for the IS onslaught on Kobanê – but also to understand why Turkey, NATO’s pillar in the region, is refusing to intervene, and why support by the ‘anti-terrorist coalition’ is so ‘timid’. Can you imagine what the Gulf emirs think of Rojava’s experiment and the principle of gender equality? And what about the Americans, the ‘Westerners’? Well, the smiling girls with Kalashnikovs are absolutely glamorous, but to the USA and the EU the PKK remains a ‘terrorist’ organisation, whose leader ended up in a Turkish prison with the cunning assistance of the former Italian PM Massimo D’Alema (the ‘fox of the plains’, as he used to be mocked). And by the way, this PKK, wasn’t it born as a Marxist-Leninist organisation? They’re all Communists, as usual.

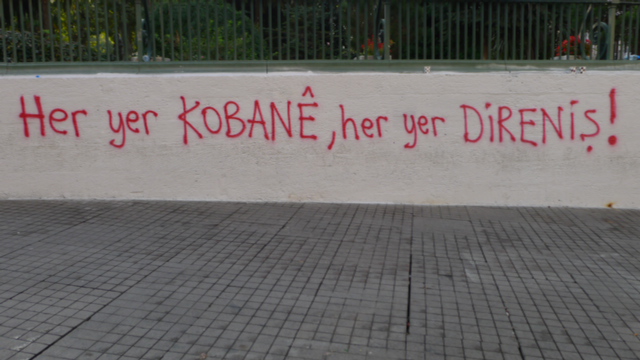

So what now? We will be the ones to defend this form of Communism, to go down to the streets and side with Kobanê and Rojava – and to reinvent, from this point, in an absolutely tangible way, our opposition to war. In Rojava we must recognise the links with our recent history; we must be ready to hear echoes of Seattle, of Genoa, of the Zapatistas. Because those echoes exist. And more than anything we must see the thread that connects and prolongs the 2011 uprisings in the Maghreb and Mashreq, that goes through the Spanish 15M and Occupy, through the Brazilian and Turkish upheavals last year — this thread runs now along the streets of Kobanê and Rojava.

War brushes the European borders today, it comes to our cities with the movement of fleeing women and men — if they are lucky enough not to end up at the bottom of the Mediterranean. With the crisis, war threatens to cause a wider stiffening of social relations and lead to an authoritarian government of poverty. War and crisis: not a new coupling. Its shapes, however, are new: in the relative crisis of American hegemony, which clearly constitutes a salient trait of this globalising period, war still unfolds its ‘overthrowing’ violence — but there are no realistic scenarios of ‘reconstruction’ on the horizon (not even those that would be contrary to our position). The incidents within the ‘anti-terrorist coalition’ are a clear example of this deadlock.

Breaking such deadlock is a necessary condition for the real success of struggles against austerity in Europe. And this will only be possible through a tangible and material affirmation of those principles of organisation for life and social relations that are radically incompatible with the reasons of war; this is why the Rojava experience acquires an exemplary character for us. While house-to-house fighting takes place in Kobanê, thousands of people demonstrate and clash with police forces in Istanbul and other Turkish cities, and hundreds of Kurds burst into the European Parliament in Brussels. It is often said that political action at European level can only be an abstraction. Now try to imagine what the situation would be if the Kurds were supported by a European movement against war, capable of mobilising people in a similar way to the 2003 demonstrations against the war on Iraq – but this time, finally, with a regional interlocutor. Are conditions not right yet? One more reason to get involved. Is this a dream? Someone said that it takes a dream to achieve victory.

7 Oct 2014