How Do You Solve a Problem Like Donald Trump?

This article has been co-written by a member of Plan C Manchester and their American partner. It is intended to contribute to broad discussions, within Plan C and beyond, about what strategies of struggle are appropriate to combat Donald Trump’s presidency. It does not reflect the views or opinions of Plan C as a whole.

‘I think both Sanders and Trump can’t be bought. Trump can afford not to be bought and Sanders has the ethics not to be bought. The entrenched Democrats are afraid of Sanders and the entrenched Republicans are afraid of Trump. I’m looking at it as a very positive thing. I think it’s a very big wake-up call. Most politicians will tell you what they think you want to hear. Both of them [Sanders and Trump] tell you what they think. Now, they say those two are loose cannons. They may be. But they tell you what they think and they don’t backtrack. In today’s government, when it comes right down to it, our president doesn’t have the last word on foreign policy, doesn’t have the last word on economics. He’s surrounded by advisors, so any candidate can be taken care of. What you need is a strong leader that can’t be bought and that’s got values. Who says what’s on his mind and won’t say something just to get voted.’ – A Trump Voter and Small Business Owner, Pennsylvania

Driving through the middle of Pennsylvania during last year’s primaries we were reminded of a well-known saying about the state: ‘It’s Pittsburgh to the West, Philadelphia to the East, and Alabama in the middle’. If yard-signs were any indication of voting habits it was going to be a clear Republican win in the middle counties. Support for Cruz and Trump outnumbered that for Sanders and Clinton by about 7 to 1. On the Republican side, Trump was narrowly winning out against Cruz. Among the Democrats, Clinton was losing out to Sanders. A particularly telling moment came to us in Susquehanna County. In the middle of a grazing field stood a 12-foot by 8-foot, carefully constructed, hand-built wooden billboard. The entire surface had been painted blue with white stars and across it in red and white were written the words ‘Farmers of Pennsylvania for Trump’. This level of near-fanatical support for Trump was an early indication of which way the state would go. When Pennsylvania made a decisive swing to the Republican Party in November, despite polls suggesting a win for Democrats, we were less surprised than most.

The ‘Alabama’ mid-section of Pennsylvania exhibits what is a growing trend across de-industrialized and rural parts of the United States. Like many Republican voting areas Pennsylvania has a long history of resource exploitation and exportation. The world’s first production scale oil well was drilled in the state in 1859. At different times Pennsylvania has been a key player in the coal, timber, mining and steel industries. Today, rural Pennsylvania has a predominantly agricultural economy that sits uneasily alongside a faltering ‘re-industrialization’ process brought about by fracking for natural gas. The American South, another predominantly Trump voting region, has a similar history of resource exploitation. A pattern of uneven resource allocation, precarious working conditions, and indebtedness now means that the American South has the highest poverty levels in the United States, ranging from 16.% in North Carolina to 22% in Mississippi. After decades of debt-financed living, county budget cuts, and crumbling infrastructure, it is no surprise that many in these parts of the United States were willing to support a candidate who promises to bring back the coal industry, to invest in infrastructure, to deny climate change, and to remove the free-trade barriers that are undoubtedly hurting small-hold farmers across the United States. Unlike Clinton, Trump (and to a lesser degree Sanders) were striking the right chord with a disenfranchised and precarious, largely white, population.

Though we emphasise the voice of the rural poor, the issues affecting the urban poor are not to be overlooked. Much has been written about the violence, inequality and discrimination America’s urban ‘underclass’ routinely faces. Yet besides easing police access to military-grade crowd control equipment little has been done in response. Since the Clinton administration slashed benefits in the 1990’s these populations – now essentially surplus to the requirements of capital – have been excoriated for being lazy and unmotivated or else employed in low-income service sectors. Little surprise, then, that impoverished minority groups across the United States are historically some of the least likely to vote.

We are by no means suggesting that these factors played the decisive role in enabling the Teflon Man to Slide into the White House; it is not our goal to provide an explanation of November’s result in this article. Rather, we use these examples to reject accounts of Trump’s victory that wish to interpret is as the outcome of a straight-forward protest vote. Like the Brexit vote before it, there is little doubt that some have used the U.S election as a medium to put a middle finger up to the status-quo but this ‘explanation’ does little to clarify the underlying structural conditions that gave rise to this desire in the first place. The idea of the protest vote stands alongside a series of suggestions of why Trump came to power that function to distract and foreclose thought: racism, sexism, fascism and ignorance to name only a few. If the primaries and presidential race have taught us anything it is that these bourgeois moralistic arguments against Trump not only miss the mark but are also liable to further Trump’s popularity among his core supporters. We know how tempting these criticisms can be. This is, after all, a man who appears to have only the slightest grasp of social conventions. A man who has flown in the face of the incest taboo on more than one occasion by admitting that were his daughter not his daughter he would consider dating her and that she is a ‘voluptuous’ ‘piece of ass’. A man who brags about molesting women. Who for a fact cheated on his first wife. Who called immigrants rapists. Who called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S. Who appears to have no qualms with history of the phrase ‘America First’ or the alt-right icon Pepe the frog. And who caricatured a disabled journalist. When his supporters claim that one of the things they like about him is that he speaks his mind it is hard to disagree with their assessment even if one does disagree with their conclusions. The uproar that each of these remarks caused among mainstream news sources during the campaign did nothing to diminish Trump’s popularity among his core support base or to prevent his ascent to the Presidency. Of course, the U.S is not alone here. One could also consider UKIP’s Nigel Farage or the Philippine President, Rodrigo Duterte. In each case a similar romance has played out between a ‘charismatic’ but abhorrent politician and an infatuated and hapless media. It seems unlikely now that goading Trump for misspelling something online or tweeting to the wrong Ivanka is likely to dent his popularity. On the contrary, the liberal media’s continued fascination with the Trump brand is only likely to be taken as further evidence by his supporters and non-voting rural poor that the media, liberals, and politicians are corrupt, haughty, and unwilling to listen to their very real socio-political problems. Again, it is hard to disagree with their assessment.

Detroit, the de-industrialized birth-place of Fordist production, voted overwhelmingly for Clinton. Trump nonetheless took the state of Michigan.

It is for this reason that we must make a move away from these ready-made explanations and towards a critique of how Trump gained support among his base, how the mainstream media got it so wrong, why the left was ineffective during the campaign, and what the left is to do now. These questions will need radical answers that reach beyond demanding greater equality or the genuine extension of bourgeois rights and recognition to all. This article is intended as an intervention into these debates. Primarily, we want to suggest a different way of engaging with the Trump-Question. Rather than losing ourselves in the minutiae of Trumpisms, we prefer to view Trump, and the Brexit vote before him, as a symptom of a secular crisis in capitalist reproduction that precedes and in in all likelihood will outlast him. This grants us a perverse kind of optimism. Beneath every slur from Trump’s supporters against immigrants, behind their calls for a wall, or their desire ‘put America first’ we are tempted to hear displaced criticisms of capitalist governmentality. The rage against free trade, immigration and the cogs of government are fundamentally and respectively criticisms of free market competition, capital’s production of surplus-populations and the resultant downwards pressure on wages, and the influence of capital on the State. We believe that this provides a more fertile ground from which to plan political action than arguments that suggest Trump supporters are foolish, racist, sexist or in some other sense ‘backwards’.

At the time of writing we are beginning to see indications of what the Trump presidency will look like: a possible U.S departure from the U.N, U.S protectionism, the removal of Obama Care and the rolling back of the Clean Energy Act all appear to be in the pipeline. We do not believe that this maps easily onto any pre-existing logic of governance or composition of social forces (neoliberalism, post-Fordism, fascism etc.). We are therefore uninterested in trying to predict Trump’s next move or in taking up defensive positions against his policies. Instead, our aim is to reflect upon and develop some of the more practical and forward-looking actions that have been suggested and that can be taken today, tomorrow, next week and over the next four years to oppose Trump by more fundamentally opposing the composition of capital that he both epitomises and which gave birth to the Trump–branded presidency.

Where to Begin?

We believe that the problem of thinking for ourselves is one of the most profound questions the left faces today. A quick scroll through our Facebook feeds or news sources assures us that we are not short of explanations of how Trump came to power or suggestions of how we might fight against him. We are, however, increasingly conscious that this abundance of communication is at risk of foreclosing rather than promoting thought. Discussions about ‘media bubbles’ were an important side-show to last year’s election. For us, the problem is not only that media bubbles protect us from views that we do not hold ourselves, but more insidiously, that through our curated and self-confirming newsfeeds we are dispossessed of the means of thinking. Our media, so to speak, does the hard work of thinking for us so that we might consume its opinions and reiterate them wholesale as if they were our own. How often have you found yourself listening to an argument, a story, or a joke from a friend that you had also read that morning on your Facebook wall? For new thought and new practice to happen we need to move beyond the hum-drum truisms that crowd our thinking. We need to critically interrogate, and if needs be set aside, what appears to be good or common sense in both their bourgeois and communist varieties. We have therefore decided to directly confront two of what we take to be the most pervasive ‘truisms’ surrounding Trump in an attempt to dispel them.

1) The ‘So THAT’s why that happened!’ approach:

This one attempts to explain away the event with statistics, talking heads, social science and theoretical analysis. No doubt, these are all necessary if we are to plan a response to Trump’s presidency. What we object to is when these conversations stop at ‘‘Well, how interesting! Trump didn’t do as badly as we thought he might with the Latino vote’. Or, ‘Trump actually fared pretty well among white women. I wonder what that says about feminism?’ It is as if the right mix of stats and facts will sap the politics out of the event: ‘It had to happen this way, because of these groups, this tendency of capitalism and those voting patterns’. We should not be in a hurry to forget how close the election was.

As Trump’s inauguration drew closer this approach began to verge on the conspiratorial. Whether or not Putin interfered with the election is of only secondary importance to us. What is much more interesting is the response that these allegations received among mainstream media sources and liberal activists where the whole debacle played out like a bad crossover between a Cold-War re-enactment society and a Scooby-doo episode: ‘If it weren’t for those meddling Russians!’. We cannot help noticing how this narrative operates to gloss over the fact that Trump has, like it or not, successfully mobilized a set of voters that feel they have been ignored for far too long. The irony being that the conspiratorial tone of the hacking scandal ensured that the concerns of these populations were once again overlooked. Despite, or because of, this fatal shortcoming the narrative appeared much more palatable to the majority than the alternative of taking seriously the problems posed by Trump’s then impending inauguration.

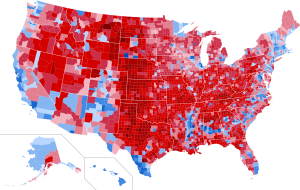

2016’s Electoral Map

By all means run analyses of voting patterns, write funding proposals for anthropological research in inner cities or in deindustrialized and rural regions of the United States, publish articles on international interference in U.S elections, but let’s push the findings further to look at the underlying causes of Trump’s socioeconomic ascendency and let’s weaponize them the best we can.

As far as we are concerned the most important statistics of this election are that over 95 million of those eligible to vote chose not to do so and that Trump was ultimately elected by a little over a quarter of those eligible to vote. Contrary to some, we do not believe that this makes Trump’s election illegitimate. Rather, it is demonstrative of wide-spread public dissatisfaction with mainstream political options and the vision that Trump has set forth for us. We should not think that it follows immediately from this that a left-wing political alternative will be better at engaging the public. On the contrary, the high level of political fatigue should remind us of just how difficult the task is that we have before us.

2) The obligatory historical comparisons

‘Well, I guess the U.S is a fascist state now!’ According to Refuse Fascism, ‘In the name of humanity’ we must ‘refuse to accept a fascist America’. In the judgement of neoconservative Robert Kagan, it is with the figure of Trump that ‘fascism comes to America’. The problem with this one is simple: historical comparisons with Nazi Germany obscure much more than they explain. They provide an easy and knee-jerk response that does not engage with the actual circumstances that befall us. We do not think that the majority of people who are drawing such comparisons are saying that Trump is the same as Hitler – at least we hope not – but it’s the distance between these two figures that matters and that needs to be investigated for political opportunity. The label of fascism is of no help evaluating this distance and has the unfortunate side-effect of once again reinforcing opposition between a moralistic liberal position and Trump supporters who are now identified as supporters of a new fascist regime. This is not to say that there is no place for historical comparisons, only that the ones recently asserted have appeared less than well formed. Make history more emancipatory by studying patterns, reading social/radical history, and engaging with the actions of historical figures focused on challenging entrenched societal issues. History can and must be used as a basis for political action, but a politics that works from equivalences for equivalences sake erases essential differences.

If there is a comparison with fascism to be made it is that, like historical fascism, Trump’s power and his danger comes from the comprehensive worldview that he provides for his supporters. Advanced capitalism increasingly imbues its subjects (capitalist and proletarian) with a sense of anxiety. Those who experience anxiety acutely will know that it has no object – it is an unlocatable and pervasive affect. Trump’s success can in part be put down to his capacity to give this anxiety an object of which we can be fearful. In so doing, he claims to put his finger on the objects that sully the otherwise pristine body of American capitalism. He alone, so the argument goes, can ‘make America great again’ by tackling immigration, ‘liberal’ climate science, the lack of infrastructural investment and the ills of international capitalism. In short, what Trump promises his supporters is a vision of American society that is not internally fissured by class antagonism. It is, of course, a nationalist argument that has the additional benefit of obscuring the real effects of this antagonism in the process. This is an incredibly powerful affective combination that has clear structural similarities to Hitler’s use of ‘the Jew’. But at this facile level one would also need to compare Trump to a great many politicians each of which, in their own way, has promised a similar completeness whether that be through the ‘big society’, Brexit, the E.U or Soviet style state-capitalism. Beyond this, we see no reason to draw any further comparison.

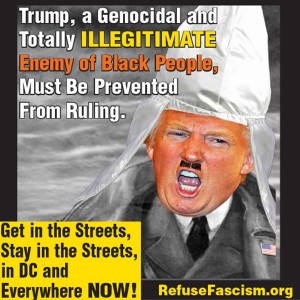

Unfortunately, this is not where the comparisons with fascism end. Refuse Fascism have taken the idea to unprecedented parodic heights. A poster on their front page has a photo-shopped image of Trump with a Hitler moustache and KKK hood beneath the words: ‘Trump, a Genocidal and totally ILLEGITIMATE Enemy of Black People, Must Be Prevented from Ruling’. Setting aside the fact that Trump was democratically elected President for a moment, we wonder how exactly these equivalences will serve to provide positive alternatives to Trump and capitalist society. From our perspective, they seem designed for only two purposes: 1) to intensify the already significant political rifts between American proletariats and 2) to call for a return to the same liberal status quo that gave birth to Trump and these rifts in the first place.

Refuse Fascism’s pre-inauguration call-out poster

More measured equivalences of Trump and fascism similarly miss their target. Judith Butler has suggested a typology of ‘old’ and ‘new’ fascisms and identified Trump as exemplary of the latter. For Butler, Trumps assumption of the power to put Clinton in jail, to export millions of ‘illegals’, and call for the re-introduction of water-boarding is indicative of the fascistic personality: ‘That arrogant indifference is what attracts people to him. And that is a fascist phenomenon. If he puts deeds to words, then we have a fascist government’. Without wanting to downplay the horror of these proposals or normalize the threats made by Trump and his supporters we would simply ask Butler what work the notion of fascism does in her politics. In the same interview Butler calls for the abolition of the Electoral College system and the two-party system. These are demands that are articulable without the idea that Trump represents a ‘new fascism’. Rather than become bogged down in the quagmire of ‘is he isn’t he’, we believe Butler’s particular strain of politics would be best served by suspending judgement on Trump’s style of governance for the time being.

Returning to Kagan for a moment, and giving credit where credit is due, we fully agree with his description of Trump as ‘a television huckster, a phony billionaire, a textbook egomaniac ‘tapping into’ popular resentments and insecurities’. But this does not a fascist make. What this makes is a hyper-opportunistic capitalist. Until further notice this is how we will interpret Trump. It is for this reason that we cannot be mad at him when he boasts about evading his taxes. He is even correct to say that doing so makes him ‘smart’. Capitalism it not a moral system. Capital serves no other purpose than its own self-valorization. As a conduit for (or in Marx’s words a ‘personification’ of) capital, Trump’s tax evasion becomes wholly understandable. As a means to the White House his trademark and paradoxical rhetorical style, which is in equal measure authoritarian and populist, has proved to be unbeatable. We are brought back to the idea that Trump is less the problem than a symptom of tendencies inherent to advanced capitalist society. We must therefore set aside the labels of the 20th century for the time being to look at Trump free of their influence. Only then can we begin to solve the problem that is Donald Trump and not the ghost of fascisms past.

What Is to Be Done?

Taking into account these considerations, we now want to analyse, critique and develop strategic suggestions that we see emerging in response to Trump’s presidency. Our aim here is to push up against the limits of what is possible from within existing strategies of struggle with the hope of moving beyond these limits. We are not providing external critiques of these strategies from the perspective of some undisclosed alternative. Though other forms of struggle have been suggested than the three we have emphasised, we believe that these are not only the most salient but that each as ramifications beyond the limited policies, movements and examples we discuss.

1) Not My President

It is clear enough that America’s Electoral College system is not fit for purpose. In 2000 George Bush successfully ran for a second term despite receiving fewer popular votes than Al Gore. Today, a President sits in the White House whose impressive victory in the Electoral College (304 to 227) masks the fact that he lost the popular vote by over 2%, or by 3 million voters. Contrary to some commentators we do not believe that this makes Trump’s victory illegitimate. A ‘democratic’ process has been followed and Trump now has a clear mandate. Those who gathered beneath the banner ‘Not My President’ the day after the election are therefore fundamentally mistaken. We are reminded of those who marched against the Iraq war with the slogan ‘Not in My Name’. Both moralistic arguments seem to do little more than say: ‘By all means go ahead with your war, become the president of the United States, but know that my hands are clean. This is not my war. This is not my president. I didn’t vote for this’. Famously, when Bush was asked how he could go to war when the (then) largest protests in U.S history were taking place against it he responded that it was precisely in the name of these people that he was going to war. He was going to war so that Iraqi’s could enjoy the same freedoms as his own citizens did to express their political opinions. If ‘Not My President’ is to avoid a similar fate it needs to pass into a kind of radical political action that takes aim not only at Trump or the antiquated democratic system that brought him to office but at the fundamental components of capitalism themselves. This will require a comprehensive secession from the apparatus of U.S Government.

A ‘Not My President’ Milk Chocolate Bar is now on sale

We therefore cannot agree with Judith Butler’s suggestion that the abolition of the Electoral College and two-party system would remedy our ailing political system. At the very least this reformist agenda would also need to demand changes to corporate lobbying, media favouritism, voting station locations and opening times, the lack of public holidays on voting days, the difficulty of voting if you are responsible for children or rely on public transport and the voting rights of prisoners. Even if all these were to be addressed we would still be a long way from challenging the fundamental economic conditions that have made, if not many then enough, turn to Trump. Our political practice needs call into question not only the organizational form of our democracies but the position of the proletariat, the composition of capital, and its dependency on producing docile, anxious and increasingly individuated and destitute populations.

We are thankful to our friends who have advanced more sympathetic assessments of the ‘Not My President’ slogan. These friends have suggested that ‘Not My President’ expresses the desire to opt out of the sovereign ‘people’ who are now to be represented by Trump. While it is too soon to tell what this ‘part with no part’ will do or become, we are sceptical that this mantra is a genuine act of dissensus and we doubt its capacity to pass over into a new constituent and sovereign moment.

2) The Women’s March

We were at once warmed and tested by the worldwide events of January 21st. The Women’s March is now the largest protest in U.S history, taking the mantle from 2003’s protests against the Iraq War. We are genuinely pleased to see so many women across America take to the streets to fight for their constitutional rights and to challenge a political institution that is blatantly threatening healthcare, reproductive rights, and equity within the workplace and society. We were pleased to see intersectional feminist theory discussed and applied and equally pleased that the march focused on not only educating women on how to be active politically but also how to be active in their community.

Despite – and because of – the positive work of the Women’s march, we want more. As miraculous as these moments of international solidarity are, the activist common sense of marching from A to B remains fundamentally unchanged from the strategies used against the Iraq War, even if the numbers in attendance have increased. This is a prototypical example what Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek have called ‘folk politics’. The problem is that these great moments of coming together – marches, occupations and blockades are all too fleeting. Each depends on us leaving our communities, our workplaces and our schools; places that might provide real leverage against capitalist governmentality. Experience tells us that once we have occupied the street or the square, the question becomes how to hold it, how to increase numbers, how to span the distance between the many different views in attendance. These questions crowd out more important questions about how to develop new and anti-capitalist sociabilities within our day-to-day lives. What we need are new, even seemingly banal, experiments with different kinds of sociability. The fact that this is a well-worn criticism of marches, squares and occupations does not blunt its applicability. Marches are useful spaces for applying symbolic power and for forming coalitions among movements but we agree with Micah White’s judgement that ‘if you’re showing up at the Women’s March on 21 January in the hopes that the world will be different on the 22 January, then you need to think seriously about the goal of marching’. It is telling that even one of the event’s co-organizers, Fontaine Pearson, began to have suspicions about the effectiveness of the march. We agree with Fontaine’s argument that we should be much more interested in what happens the day after the march than the day of it. It should go without saying that believe the ’10 actions in 100 days’ campaign to be wholly insufficient in this regard.

A poster hosted on ‘Wise Women for Clinton’ in preparation for the Women’s March

Without passing over into a general practice of day-to-day and quotidian struggle the Women’s March will have been full of sound and fury but it will have signified nothing. Unfortunately, this is where the problems begin. The unity exhibited by the Women’s March is a shallow one. It subsumes a mass of irreconcilable political perspectives under the universal category of ‘feminism’. General calls for equality are all well and good but on a more essential level we must pose a simple question: Is the core demand of this nascent movement to be about liberal equality, rights and recognition? Or is it to be about abolishing the capitalist conditions which task women with an unequal and often unacknowledged share of reproductive labour? It goes without saying that these two positions are not reconcilable. If the Women’s March is to become an effective political force it will need to decide between these perspectives. We welcome the discussions to come and believe that Plan C’s emphasis on reproductive labour, as well as the recent discussions in Viewpoint Magazine, have much to contribute.

3) Municipalism and Commoning

Alexander Kolokotonis, among others, has advanced a considerably more radical proposal around practices of communing and the municipalisation of government. Influenced by the success of municipal politics in Spain, Germany and elsewhere, these commentators argue that the city-region provides the best scale from which to strike against a Trumpist regime. Though their proposals vary, some of the most promising include drafting local constitutional amendments and ordinances to protect against Federal anti-environmental, anti-LGBT+, anti-women and anti-immigration policies.

The U.S anti-fracking movement has been using this approach for a couple of years now to some effect. In a particularly interesting case Grant Township – again in Pennsylvania – withdrew legal personhood from corporations within the township and extended them to an ecosystem. This is the first case in U.S history of an ecosystem being granted legal personhood and the capacity to defend itself in court. Grant Township has also ratified a legal right to civil disobedience against the oil and gas industry. Crucially, the legal basis for these ordinances is secured by Pennsylvania state law, and whilst they are prone to be overturned by Federal and State courts, they provide a practicable and potentially powerful way to combat Trump’s government. Similar proposals at a municipal level could include providing ‘sanctuary city’ status to immigrants and minorities. New York’s Governor Cuomo has already declared that New York State will serve as ‘refuge for minorities’ of all kinds. This could potentially provide a much-needed space of experimentation with anti-capitalist modes of subjectivity and sociability. More far-reaching proposals include developing local currencies and systems of exchange or what Truth Out calls a ‘local democratic economy’.

These suggestions are to be commended and supported. We agree that if Trump’s agenda is to be defeated it will require new organizational structures at new scales. The city-region suggests itself as one of the most logistically and organizationally sensible. For it to succeed, it will require the support of an ecology of movements and unions: Black Lives Matter, anti-Pipeline Protestors, LGBT+, Marxists, Anarchists, pro-migrant movements and more both in the U.S and beyond. In our view building this network is one of the most urgent tasks we face today.

Cities of the Future: Imagined by Eugène Hénard in 1910

We would, however, like to suggest some criticisms of how this approach is being discussed in the hope that thee limitations can be overcome. Firstly, it is clear that most municipal initiatives are developing in historically liberal cities. Los Angeles, San Francisco and Chicago have each promised to be a sanctuary city for undocumented migrants. As necessary as this is, we would like to see these programmes reach out beyond the boundaries of the city and into the rural and agricultural regions that make their way of life possible. This will require taking seriously the reasons that rural populations across America were more likely to support Trump than their urban counterparts. Without taking this step, municipal strategies risk developing liberal enclaves against Trumpism that ignore and potentially reinforce the very real socio-economic issues that contributed to Trump’s election in the first place.

On the question of commoning. Though Plan C is generally supportive of this strategy we remain somewhat critical. Our concern lies with the assumption, found in many formulations of commoning, that alternative economic systems built within capitalism are in some sense ‘outside’ of capital and capitalist relations. If such spaces were possible we would agree that the goal would be to keep producing these spaces until capital is squeezed out by a new common sense formed around a commitment to the commons. Though we agree that we should demand common spaces (housing cooperatives, common energy, war and more) and organize to establish them we should do so with the knowledge that they will exist firmly within capitalist relations and that (up to a point) they are not necessarily detrimental to capitalist reproduction. We are not convinced that common ownership of a municipal region would not relieve a Trumpist (or any) capitalist government of the economic responsibility to maintain these regions by passing this responsibility onto the ‘commoners’ themselves who are nevertheless still dependent for their reproduction on selling their labour-power in the capitalist market-place. It may be the case that we need to think of commoning as a transitional strategy adequate to the task of combating Trump in the here and now but we believe that our eye should always be on the eventual aim of abolishing the value-form altogether and with it the structural position of the proletariat.

What Now?

In writing this article we have found it helpful to think of Trump’s election in terms of what psychoanalysis calls a traumatic event. A trauma is a confrontation with something that is incomprehensible to us and which scrambles our narrative of everyday life. This would certainly explain the proliferation of arguments trying to make sense of how Trump came to power. Each one seeks to make the incomprehensible comprehensible and thus subsumable within our existing frames of understanding. This will be a task for the history books. But a traumatic event has a second and equally significant quality. A trauma is not a fleeting and immaterial event whose effects reverberate into the present. On the contrary, a trauma is a material effect with unique temporal qualities. For those who experience it, a trauma has the power to retroactively alter the past, re-writing it, and in so doing determining how we come to perceive our past, present and future. Hence, it is only after Trump’s election that one can say that the writing has been on the wall for decades – but this does not undermine the validity of the statement. 2007’s economic crash, increasing surplus-populations, de-industrialization, decreased wages, debt-financed living, mounting inequality, media-bubbles, an intensifying urban-rural divide and many more factors besides can now all be pointed to – after the fact – as contributing to our current predicament without any particular factor being decisive. This is in no way the same as saying that Trump’s election was an ‘inevitability’ from the very beginning. We should remember that he won by the narrowest of margins and that things could have turned out very differently.

Today, we act in the wake of this event; our views, practices and strategies are shaped by it. Our task must be to make sense of it, to take responsibility for it, and to organize new and appropriate forms of struggle that can strike a crushing blow against Trump and the configurations of global capital that have made his election possible. In this article we have argued that signs of appropriate responses are emerging, albeit in a nascent form, within already exiting movements across America. We are encouraged by the Women’s Movement and hope that it can have important discussions about social reproduction. We support plans for municipal actions across the United States and hope that these can lead to experimentations with forms of exchange beyond the value-form and forms of organization beyond and beneath the state-from. We even find hope lurking beneath the slogan ‘Not My President’ providing it can be taken to its logical conclusion in a constituent and sovereign moment. For these developments to happen we must set aside ready-made explanations of the Trump phenomenon, rear-guard political strategies, and activist common sense to look at the conditions that befall us today. Only then will we be on a path towards creating collectives, communities and forms of struggle appropriate to Trump’s America.