The following text was produced to accompany a creative workshop by Plan C Aesthetics Cluster at the Fast Forward festival 2018, entitled: Building New Kinds of Barricades. Over the course of the weekend, we collectively managed to instigate the spontaneous construction of three different barricades: one which accumulated on site over the course of the weekend, another constructed specifically by kids as part of the radical childcare programme, and finally a third which served as some practical foregrounding after which a version of this text was read aloud as a way of provoking some wider discussion on the nature and creative possibilities contained in the idea of building barricades. As should become apparent from reading the text, our aim in organising this workshop/exercise was to initiate some radical forms of play that are joyful and militant, characterised by different and simultaneous understandings of struggle — which centre each individual as a creative revolutionary subject but make no authoritative claims as to what any revolutionary subject might ‘naturally’ or ‘essentially’ be. The goal was to enable people of different perspectives to partake in acts of radical and collective construction, not as an act of replicating pre-existing or pre-given forms but by bringing new ones into existence. Whether this was achieved by our efforts is entirely open to interpretation, but what is certain to us at least is that this initial attempt is by no means our conclusion. Our intention is to build capacity towards future, more participatory attempts to design the partial and temporary objects of struggle which nonetheless reflect back to us the possibility of design that is radically new by dint of our collective creativity. In making this text available as a common resource we hope to inspire others to attempt similar projects of their own.

What is This All About?

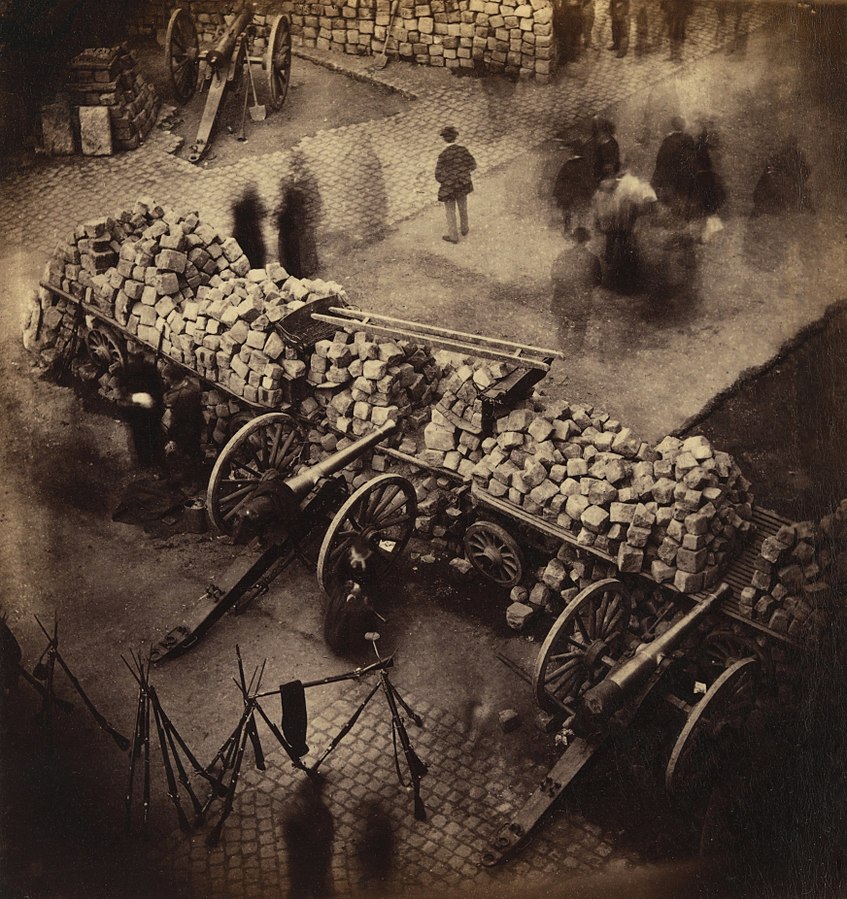

Barricades are temporary structures of fortification that emerge during struggle. They provide a kind of cover but their function is never limited to defence. More often, they are a feature of struggle towards a horizon— in other words, as part of an offensive strategy, emerging after a moment of commitment to the radical political act. The barricade provides a temporary sanctuary, to attenuate and deflect attacks from an oppressing force whilst energy and resources are recuperated; enabling space to think and reflect, but doing so in such a way that lends itself to immanent counter-offence.

The meaning of a barricade is not limited to that of being a physical structure. It is fundamentally also a piece of social and political technology. It is an effect of the needs or desires of a particular group, specifically one which has acknowledged that it is engaged in a situation of struggle, including but not limited to those situations that could be called revolutionary struggle. In the current moment it is somewhat ambiguous whether or not we are in such a situation, or who among us has a need to build barricades. If we are not in a revolutionary moment, is it still somehow the case that we are collectively under attack? And if this is the case, is there a way to justify or make sense of building barricades? We think that such a case can, and indeed should be made. In what is perhaps a more unprecedented move, we’re hopeful that the act of building barricades will in fact cast the meaning of comradeship as well as what it is we’re struggling against into sharper relief.

WTF is a Barricade anyway?

First and foremost, barricades are territorial. Territory and land are ordinarily given signification through ‘enunciating acts’ such as being occupied, owned, defended, or recaptured. Private property, for example, is identified by such ‘enunciating acts’ as being marked with borders, barriers and explicit signs saying ‘Keep Out’. Barricades function as a marker— they delimit territorial space, their presence saturates land with a zonal significance. They can mean that a given territory is safe, a temporary sanctuary in the midst of turmoil. They also betray strategic objectives. The presence of a barricade in a specific place within a given topography, such as a city district or the edge of a field, always raises questions about strategic goals. Why is it there? What is it facing? It raises further questions about whether we should give away strategic information about our intentions— if, and where we decide to build barricades can inform our oppressors of our intentions, though perhaps it is often the case that this matters far less than the need to construct them at all. What is clear from this however, is that barricades have to be robust, and thought out strategically. Not only does their emergence in a certain topographical position belie the agency behind their creation, but it also requires some justification from those agents who make the decision to construct it, with respect to its presence in a specific location, as well as the expected value of its placement there.

The deployment of a barricade transforms the significance of a territory. This is relevant even if such significance is only marginal and temporary. These structures are not so much alien objects in a territory but a proxy of our own agency, announcing our presence. Any perception of a barricade as ‘alien and imposing’ is for better or worse a political one, determined by the perspective of those on the side opposing them. It is in this sense that we understand every barricade or partition as something that must be considered in terms of its own genealogy, and never as a neutral physical structure. Border walls are barricades, just as much as the ad-hoc street partitions of May ‘68 or the eviction defenses of ZAD 2018. Asking how and why the barricade may have emerged, and which agency has caused it to arise is always essential.

Barricades in the revolutionary sense are an uncomfortable and thereby unauthorised incursion into the landscapes of vested power interests. They are inherently critical to the extent that they refuse the state and capital’s monopolies on the use of land with a direct commitment. They subvert the perspective of capital that only sees in land the possibility to accumulate through the extraction of surplus value– in the contemporary context this argument also applies to the virtual space of internet. They presume an antagonistic relationship, as to build a barricade is to already accept the reality of struggle.

But beyond just being the acknowledgement of struggle, barricades claim a collective right to space by building a structure within it, openly declaring that space belongs to the commons, not private individuals or the nation state. ‘Belonging’ should not be mistaken here to mean mere resource extraction, but also reproduction and environmental stewardship— it is nothing more or less than the commons— and we are beyond the point of attempting to bargain with its so-called owners or the regime of state violence that enforces their ‘rights’.

The privatisation of space or the ways in which it is administered by the state often serves to undermine the power required to act radically and collectively within it: the fact that generally we are not authorised to act without the permission of large companies or states undermines our sense of collective power, and as such making claims to have a right to use territory without needing the permission to do so is crucial to the objective of cultivating and maintaining a sense of collective power.

Barricades today?

Our present moment merits reconsideration of the form and function of the barricade. In many ways, its presence in our environment has waned, despite the fact that many of us find ourselves more besieged than we ever have in the past. Where barricades do exist, it is often to enclose spaces and to prevent breaching, rather than to provide offensive cover. We barricade the doors of squatted buildings pretty well, but can we think beyond seeing ourselves in such a compromised position and be bold enough to use them as cover on the streets or elsewhere?

It is far from certain that the only spaces in which we’re under attack at present are the streets, or much less that they are exclusively physical spaces. It is a reductive claim to say that we only inhabit physical spaces, because the significance of our interaction with the external world is mediated by emergent social phenomena, as well as physical, mechanical, and digital infrastructure. The theatre of struggle is also clearly no longer just one of physical confrontation on the streets, but also online, within institutions, or even within our interactions with machines and tools. How can we erect barricades to the hostile environment where the border patrol is internalised within the ordinary functioning of a hospital network as much as it is physically constituted by the plethora of walls, fences, military checkpoints, or by natural features like rivers and mountain ranges? How can we construct temporary defensive architecture in online spaces that are permeable to attacks from computer vision and facial recognition, data mining, trolls, spam, proxies, and bots? What would these barricades need to do in order to provide the specific kind of forward moving but defensive capabilities that are required to provide a sanctuary in the midst of direct confrontation, to provide cover so that injury and losses can be recouped and the struggle is fortified by solidarity as well as topographical features which are used to our advantage? Both theory and praxis are required to settle these questions and our project over the course of this weekend (Fast Forward 2018) has been to show just how porous the border between these two activities is.

Barricades are not ordinarily constructed by individuals, but are generated by a labour of collective participation. They also emerge under conditions of stress, when a group finds itself under attack– must defend itself but also launch an offensive of counterpower.

The relative absence of barricades today could be the consequence of a number of things. For one, we are more fragmented and competitively individualistic than ever. Solidarity has been eroded because of a division between people in almost every living space. We encounter one another as collections of attributes, clusters of statistical data, obstacles to our efficiently achieving ‘individual goals’, populations to be managed, nations to be defended against imaginary threats of the alien other, and most of all in a perpetual state of intense competition with one another for representation, resources, and recognition. This is by design. Such divisions are produced to pit individuals against one another, to divert our attention away from the fact that contemporary culture makes us struggle against one another over meagre fops of recognition, resource, and opportunity that are falsely claimed as all that can be offered in a world of illusory scarcity that is in actuality one of concealed plenitude. Even our ways of communicating exacerbate division from one another. We interact as clusters of data and packets of information, we look at others from the perspective of what might be useful to us in the fiercely competitive game, as something that might immediately satisfy our demands for social clout, for status, or for a fuck- but never as personal histories, as beings in a state of mutual dependency, with extended networks of affective relationships.

Our hope is that the project of building barricades collectively can help respond to the problem if it enables us to recognise our combined interest in a struggle that embodies forms of solidarity, care, and a desire to relate in ways that embrace radical alterity of the other instead of seeing them as a threat to accessing the empty rewards offered to us by capitalist modernity and nation state.

WTF is to be Done?

Ingrained attitudes to production under late capitalism will not help us in this project, because the expectation that someone is always there to provide us with the service ends up reproducing a problem of dependency upon capital which we wish to avoid. Barricades can only emerge through acts of collective labour, from the collective application of individual skills in a way that is administered democratically and not enforced by hierarchical ordinance. In the manner of anticipating possibilities for administration without the state, constructive projects of this kind must try in earnest to organise themselves around a shared political perspective and not the prescriptive ideology of a single group. Difficulties must be overcome in order to relearn and rehabilitate the practice of asking for help as a requirement of solidarity and not as a matter of exchange value, or as a trading off of interests. It is a matter of realising that labour is most rewarding when its significance is in the participation of building projects that have a collective purpose.

We need to get to grips with who or what we are defending against. Perhaps the modern decline of barricades is something we can understand as part of a pervasive and widely shared experience of domination. Late capitalism’s structures of oppression are dynamic, multiply realisable, and embedded at the molecular level of everyday life and communication in ways that become so normal that they are almost imperceptible. The totality of state and capital need not represent itself as a singular fear-inspiring entity; it achieves domination more effectively through isolating groups and meting out punishment through varied and specific forms of violence. It’s a situation which makes unified struggle difficult: how can I prioritise defence against one form of violence over others, especially when I myself am under attack.

The solidarity we aim to engender through building barricades collectively is one of ad-hoc collaboration, sharing of resources and skills, and providing our support during those moments where our comrades have the greatest need. Dissolving any essentialising definition of identity which prizes idealised notions of ‘purity’ is imminently important in this respect. We should not do this by trying to appropriate those at the margins into a larger category within which they might be tokenised or have their own concerns overlooked. We must see all of these things as in a constant state of flux, as messy and impure, but fundamentally as defined in terms of common struggle. This is to say that we ought not to erase identity or fail to acknowledge how a history of particular violence is a point of accessing struggle— we canvass here for a diversity of struggles working together and not in isolation. Collective projects have no need for any unitary movement that produces a limiting total perspective. There is a need for autonomy within collective struggle, and space for affinity groups that is not required to submit to an arch-ideology. This clears the way for new possibilities of struggling together without being reductive or attempting to level all individuals; in fact, it is essential to any non-authoritarian communist project. Such goals can only be achieved successfully through cooperation, and there are few better ways to demonstrate this cooperation than by building collectively.

The project of building barricades is a recognition that all of us who wish to exist in the margins and who refuse the agenda of reproducing only human life that is permeable to the interests of capital and data accumulation are collectively engaged in the same struggle, and need to use our resources of collective care, solidarity, shared expertise, and understanding to assert ourselves and eventually dissolve these harmful arrangements that subordinate us all. So we build barricades together, in other words, as a form of critique that is strategically necessary— and temporary.

There is here a final point about the transience of these structures that we hope can provide insight by analogy to our wider collective struggle. Much of our architecture, infrastructure, and institutions, both historic and contemporary, is designed to resist degradation, a stubborn attempt to outlast death itself. In certain cases, we need our infrastructure to last for a long time, but a neglected aspect of construction is often that of planned obsolescence, of understanding that the certitude of becoming a ruin is contained in the possibility of everything we build, no matter how relevant it is to the moment. We spent a lot of time building our barricades during Fast Forward. The logistical and physical effort in producing them was totally involving— no doubt in the same way that someone might pour their entire self into the building of a union, a political party, an institution, or even a relationship. The difficult but deeply important lesson we could learn from this is how strategically and politically important it can be to avoid too deep an attachment to the fruits of our labour, for fear that we may not be adequately prepared to move beyond our achievements. We should not be staking our future even in the continuation of a revolutionary organisation like Plan C, but looking to a point beyond when it becomes obsolete.

This does not mean that we wish for anything we build or create to be put to an end prematurely. We should also not see everything we create or build as being purely instrumental or subordinate to some abstract higher purpose. All of our collective projects have significance, and we should treat them with the utmost sincerity. An unhealthy ironic perspective we have developed from our privileged position on the timeline of history is to speak critically of things as being ‘of their time’. No doubt, anything we build now will also be of its time. The challenge for us is to realise both that our current projects will at some point be ‘of their time’, and that we currently inhabit the very moments in which they are timely, make sense, and have meaning to people.

Oddly enough, the key to producing joyful and militant resistance is to be both playful and serious, sincere and ironic, at different moments: to build things that matter to us completely in earnest and without ironic distance, only to later accept the destruction of what we have painstakingly built so that we can move forward into horizons that may only become visible because of our previous efforts. This potentially endless series of games allows us to forget our constructed ‘serious selves’ and be joyful— to stop projecting ourselves into an anticipated future that is already complete in order to liberate our actions and fully commit to what we do in the present.

This absence of a contained narrative of the future should also avoid producing static and recursive loops where nothing ever changes but we keep rebuilding. It is important to see these processes as dialectical: every iteration of our labour should advance upon what came before. We also shouldn’t lack a conception of the future— it’s just that this flexible and light attitude is different from having a rigidly fixed one. The difference is that here we are creatively experimenting and producing active responses to contemporary struggle, rather than repressing ourselves by over-theorising what the flawless and perfect objects, institutions, or forms need to be with the expectation that they can somehow transcend all of time. If the correct theory of change existed or was even knowable, politics would merely be a case of putting it into practice. But it doesn’t, and the territory ahead remains necessarily uncharted.

Failure to make peace with such facts has often created individuals who attach themselves to the future of party machines, institutionalised trade unions, or even radical organisations, producing resistance to any change in strategy or outlook even when it is sorely needed. Such a disposition can easily succumb to the pathology of reproducing oneself within an order that is stable, thereby fully reproducing it. This applies universally, whether in the case of something physical like the barricade or something less tangible like a political organisation. A consequence of failing to come to terms with the need for constant dialectical development is that we may never move beyond our barricade and find ourselves permanently stuck behind it. Clinging to it with such overwrought panic causes us to lose all sense of why it was ever built to begin with. Our future ability to struggle meaningfully depends entirely on whether we can finally do away with this tendency for good.

Plan C Aesthetics Cluster