By Ed Emery, originally published in effimera.org.

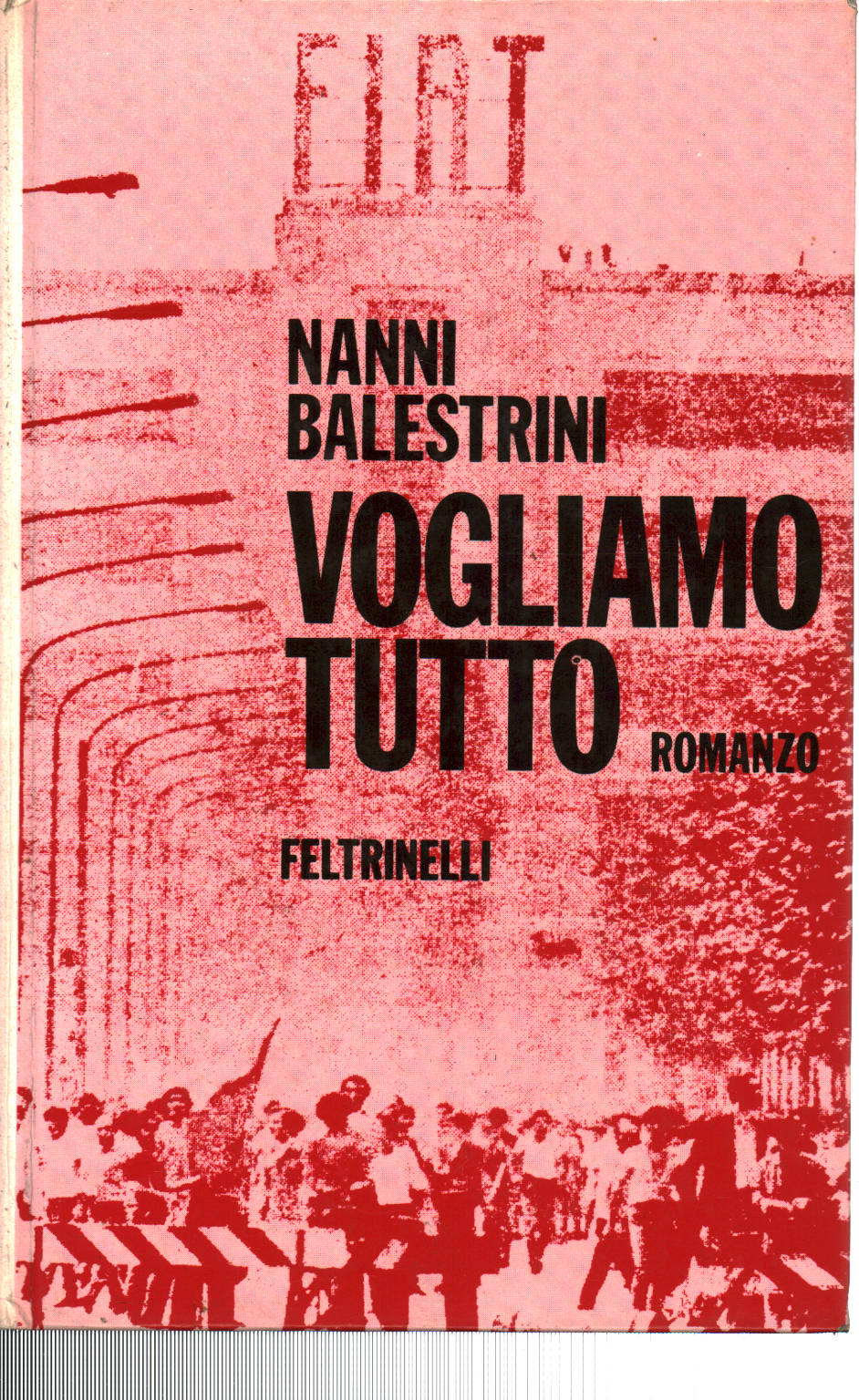

On 19 May 2019, Italian author and political activist Nanni Balestrini left us. There are many reasons to remember Balestrini. As a poet, he was a member of the neoavanguardia movement and Gruppo 63. As a prose writer, he has given us some of the best accounts of the Italian movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Vogliamo tutto (1971) and Gli invisibili (1987) were translated into English as We Want Everything and The Unseen. We Want Everything is a narrative manifesto of the struggles of the mass worker in Italy’s Hot Autumn, a workers’ inquiry at the FIAT car manufacturing complex turned into a novel. Balestrini also co-authored with Primo Moroni L’orda d’oro, 1968-1977 (1988), soon to appear in English translation. The book is one of the best historical documentations of the Italian class struggles of the time. As an activist, Balestrini was part of Potere Operaio and Autonomia Operaia, and because of this he was charged together with many other militants in the 7 April 1979 repression drive, from which he fled to France, through the mountains, on a pair of skis. As a tribute, we’ve decided to publish this text on Ford Dagenham that Ed Emery has dedicated to Balestrini after his death. It is an interesting witness to the communications among the struggles of the mass worker more than four decades ago.

London, 17 May 2019

FORD-DAGENHAM ENGINE PLANT

Workers’ Inquiry: A letter to Nanni Balestrini in the Great Beyond, a message he maybe would have liked…

A visit to the Ford Motors Engine Plant at Dagenham. The company’s birthday celebration. The occasion is the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Ford factory on the banks of the Thames – 17 May 1929 being the day that the first sod was cut.

We tour the machining area that is engaged in production of the “Panther” engine. Ultra-modern, massively automated and robotised. Each work station cost £1 million to set up, and there are many of them.

During the 1970s Ford-Dagenham had become synonymous with worker insubordination and ungovernability. This newly robotised factory is the Company’s answer to that workers’ autonomy. Under the old production system, the assembly line was a snaking single length of line, which curled in an S-shape, and was about a quarter of a mile long. The problem was this: if at any point there was an interruption, then the whole of the line had to stop. Now, out of four production lines, if one of them stops for any reason, the others can continue production. This is illustrated graphically by a large illuminated panel overhead, which shows the functioning line in green and the stopped lines in red.

In other words – no longer is it possible for workers to block the line and hold the Company to ransom. That tactical option is described (indeed, advocated) very clearly in the Ford worker’s novel that I am editing, dating from the struggles against layoffs in the mid-1970s.

____________________________

Chapter 2: ‘The marchers reached the front suspensions. But now there was no turning back. Everyone knew the consequences of that. They would fight on. But how? I looked at Steve, and he looked at me, and then we looked around at the others. Art and his mates didn’t seem to have any ideas either. It was fast becoming a tricky situation. The young Asians were talking among themselves. One was quite excited. They were looking over at the whites and the blacks now. Rai, the one who’d come up to me before, came over again.

“Listen, we have to keep the lines stopped all night. They might put some other blokes on our jobs.” Then he spelt out his plan. It was simple. “We go down and stop them driving the cars off the line.”

“You mean block off the drive-off area?” Steve caught on fast.

That was it. The only answer. So everyone rallied and marched off down through the lines with a renewed vigour. Past the foremen’s desk, across in front of all the Trim lines.

We arrived at the drive-off area. The drivers were standing leaning against a steel roof support, having a smoke. They looked startled at the sight of thirty men marching up. Steve and Joe hauled a huge wooden barrow across the Slow Line. It was full of rubber cushions. Joe and two of his mates promptly climbed in, lighting up cigarettes.

I went over to the Fast Line with the young Asians. Rai and I locked all the doors on the next car off. It was moving along on a ground floor track. The next car behind it was bumping into it. The floor track suddenly stopped. I thought someone must have pressed the stop button. But no, someone had done something more permanent than that.

Nice one! A huge spanner was jammed in the track. I looked over and saw Steve with a glint in his eye. He looked smug…]’

____________________________

There are very few workers to be seen. I watched as one worker was engaged in receiving engine blocks on the assembly line. His job was to pick up a plastic oil-filter bowl, screw it into place manually, and then reach down an overhead tool to complete the screwing process, to the required torque (torque is always a critical factor in this kind of production). Why was he there at all? Presumably only because the Company judges it too expensive to have all of those functions incorporated into a robot.

Elsewhere I watched a robot arm in operation. The engine block arrives in the crib. A sealant has been applied to three parts of the block. As it arrives, a robot arm, equipped with an ordinary paint brush, makes three descending circular sweeps of the relevant areas, in order to wipe off excess sealant. Then it pokes the brush into an upper slot in order to be cleaned of the excess. A simple repetitive task. Performed elegantly and with 100% accuracy every time. You could suppose that it is good that this mindless work has been assigned to a robot rather than a human. Incidentally, the robot is “proximity-aware”. If you come close to it, it slows its activities in order to avoid possible accidents.

Most of the vast Dagenham auto-producing plant has been shut down (Body Plant, Press Shop, and Paint, Trim & Assembly). Razed to the ground It is being bulldozed even as I write. In part this closure can be ascribed to the ungovernability of the workforce – in short the “refusal of work” that was both theorised and practised in the 1970s. Labout fought capital to a standstill. Ford always said that if things carried on like that, they would shut up shop. And so they did.

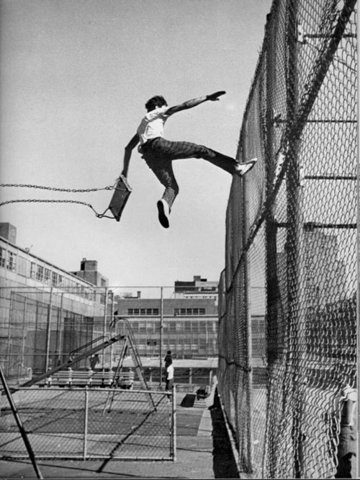

The last time that I was inside a Ford plant photographing, I was arrested. That was in 1977, during the occupation of the factory related to the layoff disputes. Those photographs were eventually published in “The Worker Photographer”, a broadsheet that I produced together with photographer Terry Dennett, and which also provided the material for an agitational Ford Workers’ video.

This time I found myself free to photograph at will. I was accompanied by a member of Ford’s staff, an Irish woman by name of J. She was helpful and courteous in all matters, asking the workers for permission before I photographed.

That Irishness turns out to be a significant aspect of the class composition of the plant. On both sides (management and unions) many of the people that I met declared their Irish ancestry. The Irish seem to be everywhere. Considering that the main body of the Engine Plant workforce was Asian for many years, this suggests an element of racist selection. Among the (very few) workers on the shop floor in this section of the factory there are still Asian workers, although it is hard to gauge the percentage. In line with diversity policy, there was a Muslim prayer room (located next to the toilets). There are now three prayer rooms, located elsewhere – one Muslim, one Hindu, one Christian. One operator speaks of his Asian colleague who disappeared for an hour each week for Friday prayers.

A young woman by name of G. speaks of her family’s history at Ford. She is a fourth-generation Ford worker. She too is of Irish ancestry. She explains the brutality of Ford’s hiring system in the early days. When the completed factory opened in 1931 (bear in mind, in the aftermath of the great financial crash), the Company brought 2,000 families from its former manufacturing plant in Trafford Park, Manchester. Transferred them to Dagenham. As G. explains, in the old days the men would arrive each morning for work, and would wait outside, waiting to see if they would be picked. The same iniquitous system that applied in the docks. Her grandfather did not achieve permanent employment until 1952.

_________________________________

FORD MOVES FROM TRAFFORD PARK

As told by Walter Greenwood in There Was a Time [Penguin Books, 1969], the birthing moment of the new Dagenham plant was a moment of worker violence. He tells of the Henry Ford’s visit to the UK, and the chief Ford employee who visited the Trafford plant immediately prior to the company’s operation to move 2,000 families from Manchester to Dagenham:

“From afar came rumours that a sudden visit from Him was imminent. […]

“This time, though, all doubt was banished. He was on his way. All the newspapers carried photographs of him stepping aboard a translatlantic liner, the King of Mass Production accompanied by his Baronage, the Heads of Departments. Big men, tough men who had bullied their way to power and who held on to it by the exercise of unremitting ruthlessness. King and Barons alike, the newspapers said on their arrival, were come to see the company’s vast new works now in process of construction on the Thames’s lower reaches.

“All in the Manchester works, which now was to be superseded, were on tenterhooks. Works and office managers, taut and sweating, communicating their irritability to under-managers, foremen and Spot the Ball who, in turn, took it out on the lower deck. When would He come? No sign, no news, a prolonged and charged expectancy until all felt like prisoners in the dock waiting the tardy reappearance of the jury.

“In the event Himself disdained visiting his Lancastrian territory. In His place a Baron, armed with full authority, was dispatched to examine the personnel eligible and worthy of transfer to the South.

“Absolute power, being a bully, attracts its like. He who came in place of Him wore the purple with brute arrogance. Of Scandinavian extraction, he was oversized, ham-fisted and excessively muscular. His contemptuous, transatlantic nasal bellowings had our intimidated superiors on the skip and jump, though not all employees of low degree were impressed. On his progress through the main assembly shop the Ambassador, making a random selection from the workmen, picked on the wrong man with the question, ‘Say. You. Would you work harder if you were paid more?’

“‘I suppose so,’ the man said, unsuspectingly.

“‘Fire him,’ the Ambassador said to his aide, then received a lesson in the dangers of pushing a man too far: he was sent on his back, spitting teeth and blood. The sacked man flung aside the twelve-inch monkey wrench and, without further parley, made for the main gates and the dole queue, a familiar path so many of us were soon to tread once again.” [pp. 156-7]

[Trafford Park had become non-viable because of problems of transportation – the old canal system could not handle the volume of freight. Therefore Ford decided to transfer southwards, to the marshes of south-east Essex. In addition to the new factory he built a deep-water terminal on the Thames in Essex, to allow for mass importation of raw materials and the export of its cars to the world at large.]

__________________________

Until the end, I kept quiet about my militant activities at Ford in the 1970s. But then I fell into two separate conversations with Ford men who had also been my guides during this visit. One of them turns out to be an unofficial historian of the factory, and has gathered several hundred old photographs of the factory during its years of development and decline. And the other is a working-class archivist and a card-carrying communist (in the sense that he likes to be photographed carrying his copy of the Morning Star).

It immediately becomes obvious that we have much to discuss and much to share. I have the militant history of those days in my archive, and they have the history from the Company’s point of view, and from the Union’s point of view. We discuss potential points of collaboration.

I am strongly tempted to begin a process of “workers’ inquiry” into those hot years of the 1970s and 1980s. Oral history. To see what interesting material we can unearth.

I shall inquire among like-minded comrades to see if anyone will be interested to join me in this venture.

By the end of the visit, and by a curious quirk of destiny, I was invited to help cut the square Ford birthday cake with its blue icing and white lettering.

Arising from this visit, I am now working to produce a short film, using the photographs gathered today. It will be entitled “The Worker Photographer”, and it will be dedicated to the memory of Terry Dennett, and also to

“all the poor buggers who wound up dead

because the system ground them down-oh…”.