By Leopoldina Fortunati

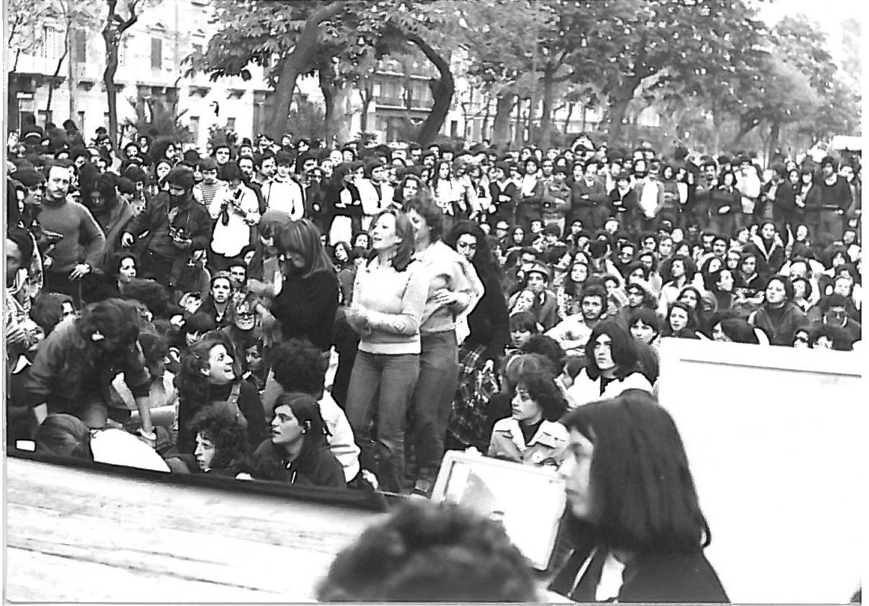

On 8 March, Women’s Strike demonstrations were held in Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Leeds, Liverpool, London and Plymouth, while massive International Women’s Day mobilisations were taking place across the world. On 9 March, women’s strikes were also held in a number of countries including Chile, Argentina, Spain, and Poland, with the highest turnout and economic impact in Mexico. On this occasion, Plan C has asked social reproduction theory pioneer Leopoldina Fortunati for her reflections on the current political situation. Fortunati began her activism in the context of workers’ struggles in the 1960s and 1970s in Italy and was a key member of Wages for Housework. She then became the author of the classic book The Arcane of Reproduction: Housework, Prostitution, Labor and Capital (1981), and – with Silvia Federici – of Il Grande Calibano: Storia del corpo sociale ribelle nella prima fase del capitale (1984).

Over the last decades, women and the youth have deeply innovated politics: from ways of thinking and communicating political discourses to emotional approaches to militancy, from attitudes towards organising to expectations towards political behaviours. In particular, in the late 1970s, women moved from focusing on what was wrong in their lives – feeling as victims – to acknowledging their responsibility towards what was happening around them and becoming conscious of the massive power in their hands. This happened thanks to the young generations of women. If the analysis merely revolves around the evils of capitalism and blaming everything on capital, it becomes impossible to understand neither our own potentialities nor how much capital was interiorised by us all. Women realised that it was necessary to shift from a disempowering, reactive and negative attitude – typical of militancy in traditional parties and movements, and leading to gloom and discouragement – to an empowering, proactive and affirmative posture.

It is in the interest of men to side with and support women in their mobilisations. Let us take a look at the current situation in the sphere of reproduction. The feminist wave of the 1960s and 1970s helped the women of my generation as well as the following ones to achieve more power in the family and in society, which means more civil rights not just for women but for men too, a stronger sense of participation, an increased freedom to move autonomously, especially in formerly industrialised countries. It is however necessary that everybody, women and men, realise that if the question of reproduction and the female condition are not addressed – for what concerns the recognition of the value that is produced here, in economic, normative and cultural terms – such a sphere will keep functioning as a thorn in the side of the whole working class, in a destructive race to the bottom.

Up to the 1980s, the driving force of political, organisational and technological initiatives was the sphere of commodity production, understood not only as the production of material goods but also and increasingly as the making of services. From here, processes and behaviours were transferred to the sphere of social reproduction, which had to function and produce in a dependent and auxiliary fashion. It was a trickle-down mechanism in which initiatives and practices moved from the sphere of production to that of reproduction. Such mechanisms, at least in formerly industrialised countries, were completely overhauled, because now the sphere of reproduction becomes the model that is exported to the system as a whole. The fundamental characteristics of housework and care work – e.g. unwaged, precarious, scantly regulations and absent of collective union bargaining and party representation – have all been exported to the sphere of production, where they have become less abnormal relative to past decades. Forms of the regulation of social relations that were formerly considered as secondary or peripheral – tolerated only in the sphere of reproduction – entered in competition with more unionised forms of social contracts. The new generations paid a high price in terms of precarious and/or informal employment, more or less forced migration, lack of economic independence from their parents, and the impossibility – in such conditions – to live with their partner and have kids (if desired) feeling secure.

However, not only were weaknesses exported from reproduction to production, but also ways of negotiating power relations that were originally developed within the family, between women and men as well as across different generations. For example, the anti-authoritarian stands of children and the youth against their parents, developed inside their families, have inevitably reshaped how the new generations of workers demand to be treated in their workplaces. As parental authoritarianism in the family eased, the new generations of workers gained a more respectful treatment in their workplaces. Today, in many cases, the bosses need to address the workers politely (“Could you please…”) if they want anything to get done.

Individual and social reproduction have completely changed. Formerly, they were considered by the traditional organisations to be loci of political backwardness, now they have become the beating social and political heart of the capitalist system as a whole. Reproduction has emerged as an immense laboratory of social and political experimentations, dangers, dreams, initiatives, and visions. The sphere of reproduction is where movements such as the Arab Uprisings, the Indignados, Occupy, and initiatives like Urban Knitting, Se non ora quando, MeToo, the Women’s Strikes, the Climate Strikes, have developed in the latest decades. The sphere of reproduction is where the future is weaved, discussed, and imagined for the long term, in real and sustainable ways. In the formerly industrialised countries, women, men, children, youths, adults, and the elderly are experimenting with different forms of gender, to shape their paths in autonomy and self-determination. The old gendered division of labour and the resulting differences between women and men – based on the equivalence between women and femininity and men and masculinity – have undergone many a social and political change.

I would like to focus on what I call the “Movement of the Concrete” to explain the potentialities for experimentation existing in the sphere of reproduction today. The Movement of the Concrete has a broad social composition, it is constituted of everybody who wants to begin building a new world in the here and now, without waiting for the collapse of capitalism or focusing exclusively on how to destroy the current system. This mass movement aspires to assert a playful counter-production, counter-consumption and counter-reproduction beginning now, and not “after”. Its political programme is one of collective liberation, starting with the liberation from the mandatory sale of labour-power in the market with the associated global capitalist discipline, control and exploitation. The primary and crucial site of liberation from capitalism has changed, it is now the community and the earth, inhabited by women, men, youths, children, elderly, sick, disabled… all of whom are considered as political subjects.

The Movement of the Concrete encompasses emotions, passions and affections in its development and in its political culture. Its participants have rediscovered – learning from the politically “residual” figures of the dilettante, the volunteer and the housewife – the role of emotions, self-expression and creativity in their work and in what they produce. It is not by chance that bricoleurs used to be called “dilettantes” [enjoyers, editor’s note], to signify how they are moved by a passion, and therefore pleasure and playfulness are the motives of their work. Dilettantes traditionally worked in their homes or garages, transformed into small workshops. Another social figure motivated by emotions is that of the volunteer. In this case, the motive is compassion and the desire to help those who are in need, but volunteers feel pleasure in caring for others. No doubt, the dilettante and the volunteer are strictly related to the figure of the wife-mother-housewife, whose work was constructed as love and affection. Housework was always motivated by feelings and emotions, and it has always represented the emotional and psychological management of affections, caring, protecting, nourishing, comforting and supporting all family members. In this type of work, alienation is due to the commodification of emotions and affections, the lack of acknowledgement of the value of such work and, consequently, the lack of social respect that goes with this.

In the political perspective of the Movement of the Concrete, liberating work from the yoke of capital requires and implies liberating it from alienation, understood as dehumanising non-emotion and disembodiment. Little by little, these processes are demonstrating that it is possible to produce without bosses, through relationships of cooperation and solidarity, without alienation and self-exploitation. The participants of the Movement of the Concrete are far from being merely concrete thinkers-creators. They have now the possibility of bringing together the science of the concrete and that of the abstract (that is, the contributions of engineers and scientists) in a relationship of mutual support. Women and men are preparing to know what to do and how to do it when capitalism falls under the weight of its own structural contradictions and the political maturity of the multitudes.