By Katie H

Mutual aid responses to the pandemic have the potential to develop into new, locally controlled institutions outside of the neoliberal economy and thus form counter-power to both state and capital.

The Covid-19 pandemic is rapidly devolving into a vast multi-faceted crisis of social reproduction. The staggering incompetence of international and national governments at protecting our fragile public health systems (those that have clung on after decades of austerity and neoliberalism), and enabling their workers to keep people alive – let alone stay safe, fed and protected – has been unveiled.

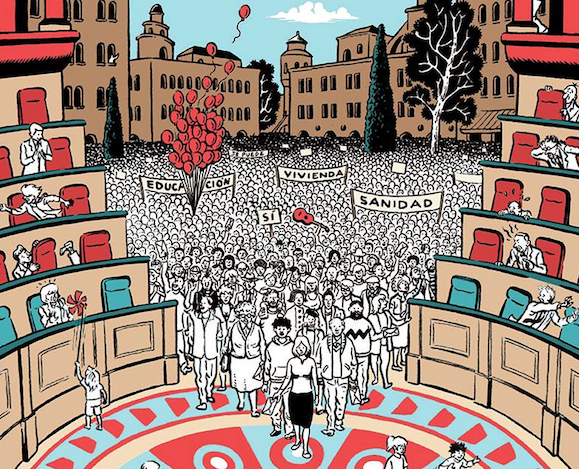

It is clear that we need rapid mobilisation of infrastructure and resources in order to sustain our livelihoods and communities in the short term. But beyond this, we on the left need to set our sights on creating a new commons through the expansion of community, worker-owned and managed cooperatives and, ultimately, the expropriation of private assets. This cannot be achieved through militant political activism alone, but through building counter-power from below.

Solidarity, not charity

Mutual aid builds confidence and capacity among communities to organise themselves in order to meet their own needs. At the same time, it produces tangible local ‘victories’ in the everyday struggles people face under capitalism. Seeing these result in improvements to material conditions means people are more likely to get involved and believe in the possibility of radical change. Similarly, a political movement that offers genuine and immediate support in the face of rampant landlordism, gentrification and miserable working conditions, at the same time as holding a broader long-term vision for a better society, is more likely to gain trust. To make genuine progress towards a transformative politics, we need a model and method for organising that can both respond to the real challenges people face and help overcome the pervasive cynicism about prospects for radical change amongst wider society.

But how can we use this moment to build autonomy and forms of collective power that make us strong enough, not only to survive,but to build a new world as we continue to witness this one crumble?

Dual power strategy

A dual power strategy is one in which a broad section of society becomes organised in such a way so that autonomous institutions, democratic structures and cooperative economic base can be built as an alternative and act as a counter-power to capital and the state.

The Jackson-Kush Plan, initiated by Cooperation Jackson provides one such example. Developed by community organisers from the Black Liberation Movement as an initiative to “build a base of autonomous power in Mississippi [….] that can serve as a catalyst for the attainment of Black self-determination and the democratic transformation of the economy.”

The plan is based on the principle that political self-determination is not possible without economic self-determination – that a grassroots movement must focus on building autonomous power for achieving both. Through democratically run cooperatives and community land trusts, Cooperation Jackson has become an important political force in the city, able to push back against gentrification whilst promoting economic and political self-determination for marginalized communities.

In addition to organising from the bottom up, Cooperation Jackson put forward progressive political candidates in local municipal elections in order to create a culture of direct democracy. Just how far a social movement is willing to engage in electoral politics is a tactical question that can come at a cost. Even at a local level, where candidates might be selected by and accountable to local assemblies, electoralism can be a drain on resources better spent on creating radical infrastructure and must be embarked upon with a healthy dose of caution and skepticism. Fundamentally, dual power conceives of creating a political space outside the electoral one and autonomous from the state.

The Democratic Confederation of North East Syria (formerly known as Rojava) provides a larger scale example of an organised building of counter-power across a vast area inhabited by 2 million people. Here, building on decades of struggle, the Kurdish Freedom Movement rapidly helped set up and establish communes of 30 – 400 people (depending on the size of the village, town or city) stretched along the 400km border with Turkey. Each operates a male and female co-chair system and composed of mixed ethnicities from Kurdish, Arabic to Assyrian. These communes are responsible for organising the needs of the community and send delegates to larger neighbourhood, district and area assemblies, all the way up to the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria. Confederalism, theorised and practiced by this liberatory, anti-colonial struggle, can provide us with a template for a revolutionary strategy that aims to build a radically democratic, ecological, feminist society on a mass scale.

Bringing it all back home

How such a politics might look across the Isles of Britain is uncertain. It must be responsive to the needs and conditions of differing local communities torn apart by decades of neoliberalism and ten years of crippling austerity. The key strength of such a movement would be in its ability to address economic and political differences on the local level, whilst still being able to form networks and even confederations at national and regional levels.

Cooperation Town is one such initiative set up by community organisers and residents. Its aim is to establish a network of self organised, community-led food co-ops on housing estates in every town. Local co-ops are run by members, who decide collectively what food to buy, how much and how it is distributed. Since starting the project last year, they worked to scale up the network through training and mutual support, before rapidly adapting and utilising the infrastructure they’d already created in order to respond to the Covid-19 crisis.

A dual power strategy recognises that only by establishing an autonomous, community-led and cooperatively-owned economic base will communities be able to respond with sufficient strength and resilience when the state fails us and we face yet another financial collapse. In the face of climate change and impending ecological catastrophe, we need to be thinking further and beyond, towards reclaiming common spaces for localised food production and shelter, for example.

When the moment comes for a new genuinely broad-based movement to emerge in the UK, the revolutionary left needs to have the infrastructure in place ready to make sure it is not co-opted and remains explicitly political. As Plan C has argued elsewhere, we must resist attempts to recuperate this movement into liberal forms of ‘good citizen’ initiatives, self-help activism or charity. This requires that we educate ourselves and each other about political economy, the prevailing ideologies of neoliberalism and patriarchy and the rich history of grassroots and democratic alternatives, as well as direct our effort towards setting up autonomous social and economic institutions.

We must continue to emphasise that mutual aid is a political response to the inadequacy of the government and the vast inequalities and failures of neoliberalism. But people will only start to believe that another world is possible when they see it being built before them. Dual power is how we build that world.