By Sergio Ruiz Cayuela, a Plan C member. Originally published in Pirate Care.

Covid-19, a “not-so-natural” disaster

The global Covid-19 pandemic is being faced by governments and covered by the media as a natural disaster. And in a way they are right: as scientists predicted, the rapid change in climatic conditions has created a favourable environment for the virus to spread. However, other factors have also contributed to the transmission and mortality of the disease. Global capitalism and the frenetic movement of people and goods that it entails; an endemic lack of funding (or plain privatisation) of public healthcare systems all over; cultural inclination to frequent socialising; and, most importantly, widespread lack of access to basic goods such as healthy food or clean water and air. Critical geographers already discovered decades ago that natural disasters are not purely natural, but to a great extent they are socially constructed. Or as Neil Smith, in his account of Hurricane Katrina, puts it – natural disasters don’t just create indiscriminate destruction, “[r]ather they deepen and erode the ruts of social difference they encounter”.1

From disasters to solidarity

But there’s a more hopeful side to natural disasters which seems to be reproduced across temporal and geographical scales: the outstanding popular responses based on solidarity and cooperation. In extreme situations in which the social order is temporarily broken, people tend to organise together in order to fulfil each other’s basic needs and ensure their collective survival.2 Whilst there’s goodwill in all the help being offered, the current pandemic is proving that it’s not enough. A clear lack of experience in political involvement and structured organising by most of the population is decimating mutual aid efforts in the UK.

Take as an example WhatsApp groups created to connect residents of the same street or area in several cities, which have become the locus of popular self-organisation in times of Covid-19. Whereas they might be useful to help some people in self-isolation to access basic goods, their reach is very limited. They embody a type of solidarity which, even if necessary, is insufficient because it is exclusively based in locality, which is translated in a lack of coordination among networks. Moreover, unequal access and ability to use technology or lack of time to follow conversations are factors that, when not taken seriously, prevent many community members from being actively involved. In the end, these groups tend to be taken over by a few residents who dominate the interactions and/or modify the scope of the group – and with it its potential effectiveness.

How to organise a solidarity kitchen

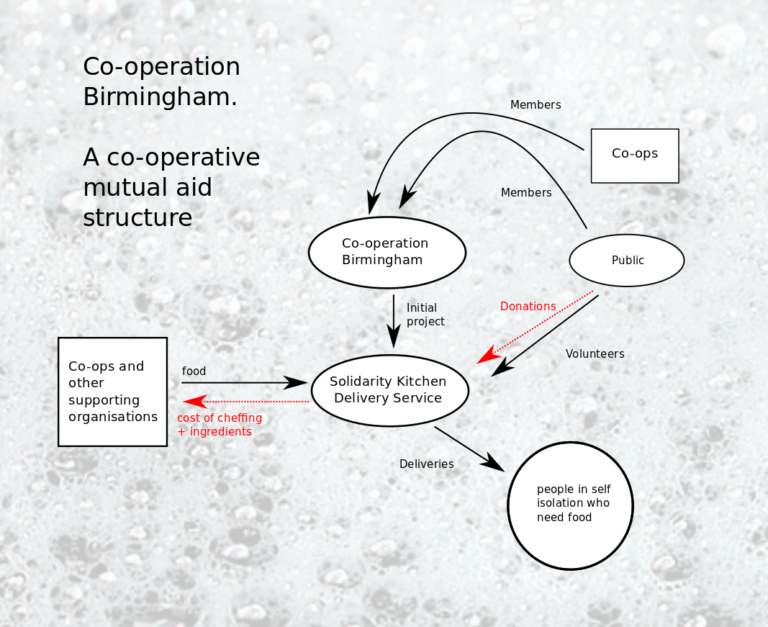

Aware of these dynamics, and of the fact that structure and purpose are key factors in mutual aid efforts, Cooperation Birmingham3 has recently brought together several grassroots organisations and workers’ cooperatives to create a solidarity kitchen. Funded with donations collected through an online platform,4 we offer warm meals to people in self-isolation in Birmingham. We ask no questions and we take no money, we practice solidarity without conditions.

Securing access to a professional kitchen

Two infrastructural dimensions are basic in the organisation of the Cooperation Birmingham solidarity kitchen: physical and political infrastructures. As obvious as it may sound, in order to provide cooked meals you need a kitchen. The bigger and better suited, the more meals you will be able to provide. Key to the success of the project, thus, is the participation of the Warehouse Cafe, a centrally located cafe, organised as a workers’ cooperative and home base to several leftist and environmental organisations. The temporary closure of the business when the pandemic started has given us access to a professional kitchen.

Social measures encourage solidarity

Not only that, but many of the cafe workers (including the chefs), who are currently furloughed, are contributing with their labour to the project. In addition to the cafe workers, over 40 people contribute regularly to the project by cooking food, cleaning the kitchen, delivering meals, and doing backroom work. This constantly expanding group is mostly composed of people who are not able to engage in waged labour in the current situation. This fact shows the real importance of adopting social measures directed to covering the basic needs of workers, as they encourage solidarity and mutual aid and have an impact that surpasses economic calculations.

Organising – horizontal, practical and open

As for political infrastructures, the experience in organising of most of our members is key for the success of the project. We work on an ideally horizontal but practically layered structure of decision-making, in which decisions are made by a mix of consensus and pressing-need. The main decisions are made in open online meetings that usually take place three times a week. For smaller issues related to the daily operations, we have created working groups with a certain degree of autonomy and specific tasks assigned. The assessment of the operations in the open meetings allows all members to reflect on the general direction of the project, but also on specific practical matters.

Thus, the fluid interaction between open meetings and working groups avoids the accumulation of power and ensures that the political orientation of the project remains in the correct path. It is important to acknowledge that all political infrastructures are open, and we encourage both volunteers and users of the kitchen to join a working group and attend to the open meetings.

Communication

Crucial for the correct functioning of our political infrastructures is technology. We have an open online forum5 where whoever is interested in joining the solidarity kitchen, or just curious about it, is able to see at a glimpse the form of our political structure, join a working group, and read the minutes of the meetings. We also make use of social media, which is key for ensuring transparency, reaching new users, and recruiting volunteers. And, of course, instant messaging apps provide a much needed bridge between political and physical infrastructures.

Councils externalising social services onto the commons

As nice as it may sound, our solidarity kitchen is far from perfect, and we try to learn from our mistakes and fill our gaps. It has been difficult to deal with a huge workload and different levels of involvement that have led some organisers to the edge of burnout very soon. However, we have been put in a very difficult situation by the Birmingham City Council, which is denying responsibility and relying on the commons to respond to the crisis. Instead of setting a relief operation of sufficient scale that would reach most of the vulnerable population in Birmingham, the City Council has been directing people to community efforts like ours. After our second day of operation, the council started referring calls to us, which meant a surge of over 500% in food requests from one day to the next. At the same time, we received a call from a council worker offering support to our solidarity kitchen, but our scope was always filling gaps, not taking over. Since then, we have had to cap food deliveries at around 100 daily meals and we are trying to involve new members and recruit volunteers to ensure the sustainability of the project and a controlled expansion. In this situation, we are overburdened with a responsibility that should not fall on us and is disproportionate with our capacity, which has a toll on our physical and emotional well-being.

A perspective beyond the current crisis

At the same time, though, this systemic externalisation of social services onto the commons makes the existence of politicised mutual aid projects like ours more important than ever. Because our purpose is not just to respond to the current crisis, we need to look beyond. What awaits after the immediate public health emergency is an economic crisis of unprecedented magnitude that will change the capitalist system as we know it. Socio-economical reconfigurations that follow disasters and crises traditionally offer “an opportunity for elites to recapture and even intensify their power”.6 However, there’s also a window of opportunity that we should try to seize. We need popular mutual aid efforts such as Cooperation Birmingham to become strong alternative institutions that take power from political elites and redistribute it among the working class. We need to have a major role in writing the new rules of the world to come. A world defined by the worst economic crisis of our times and by climate change, an uncertain world in which the elaborate system of social ordering will start to crack.7 A world of hope.

Notes

- Neil Smith: “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster” ↩︎

- Rebeca Solnit (2010). A Paradise Built In Hell. The Extraordinary Communities That Arise In Disaster. Penguin Books. ↩︎

- https://cooperationbirmingham.org.uk/ ↩︎

- https://www.gofundme.com/f/cooperation-birmingham-mutual-aid-kitchen ↩︎

- https://forum.cooperationbirmingham.org.uk/ ↩︎

- Ashley Dawson (2017: 257). Extreme cities: The peril and promise of urban life in the age of climate change. Verso Books. ↩︎

- John Holloway (2010). Crack Capitalism. Pluto Press. ↩︎