By Felix del Campo, Plan C London

This text was written as a series of reflections on a year-long pandemic intertwined with conversations with comrades about love and revolution. It moves in time with no particular chronological order.

This is a longer text, so we have made efforts to increase its accessibility. We have made two PDF versions, a LARGER TEXT VERSION and A PRINT READY VERSION. We will also be producing an Audio version as part of our Podcast.

It’s 27 of November of 2020. Temperatures in England have dropped drastically. Crispy fog thickens morning dew, Londoners rush through their early routings of jogging in the parks that have become, for many, one the few mechanisms at hand to hold them hanging from a very thin rope to mental sanity, a compulsory run before a long day of working from home in precariously improvised offices in kitchens full of noise, kettles fuming and flatmates competing for the broadband to attend zoom meetings back to back and panic if the network is not stable, pretending that things are normal and expecting to deliver as such, maybe hiding their unprofessional workspaces with a neutral background while part of their faces melt in the blue sky of a Hawaiian beach, almost like the melting of days into days of a routine that has shown its unbearable dimensions when the whole system of “out-of-work” everyday activities that holds it together, transferring some meaning away from whatever bullshit job that is obviously meaningless, has stopped indefinitely. Or kids dying for attention, the third lockdown schools are closed and their carers need to convince their kids that even when it doesn’t seem the case, attending class and keeping up is not an option but a duty. Carers that also work in front of still impersonal Hawaii backgrounds. And that’s for those of whom lockdown has meant this. Many have kept with their usual lives, going to work every day: key workers, essential workers ( fancy words now) going with their lives as usual only that now the usual has become a weird acceptance of a higher risk than usual. But we are used to risk anyway, I mean, do we want the nanny state to save us or something like that? We must be crazy! we must be deluded, MAD! And yes, it is true that some others could not even socialise at all. Another socio-economic category that was trendy back in March 2020 but that at some point, maybe forced into isolation as a matter of life and death (and let’s be honest, it is a pain in the ass to deal with this within a system and with a government that values production and consumption over care and social responsibility, isn’t it?). They have been rendered invisible, almost as if it was never about them and us, all together into this. Almost as if, as my comrade wrote, they have been termed as “excess lives” that would die anyway, almost as if thinking about the intricate network of infinite exponential human connections has become totally impossible to conceived in our mind, a socialist utopia not mediated by exchange value and so divorced from the Real Reality of things, that it is rejected immediately as infantile wishful thinking, while hordes of nihilist libertarian left and right monsters populate our nightmares, liking through this break in the tissue of society, time adding to the erosion making these fractures a more serious matter.

It’s 25 of November 2020, someone shares a story on Instagram that reads in Spanish: “When you lost your job, your house, your democracy and your most fundamental human rights…but you didn’t care because your government saved you from a virus with a survival rate of 99.6%”. This text frames a picture of someone with his hand on his chest in a pose of release. Over him, you can read the word “thanks”. If the form of the social and political order is intrinsically related to the form of the economic relations that are produced and reproduced and limit the extent of what is possible and even thinkable, we just need to erase Society and those complex relations become unrepresentable in your mind.

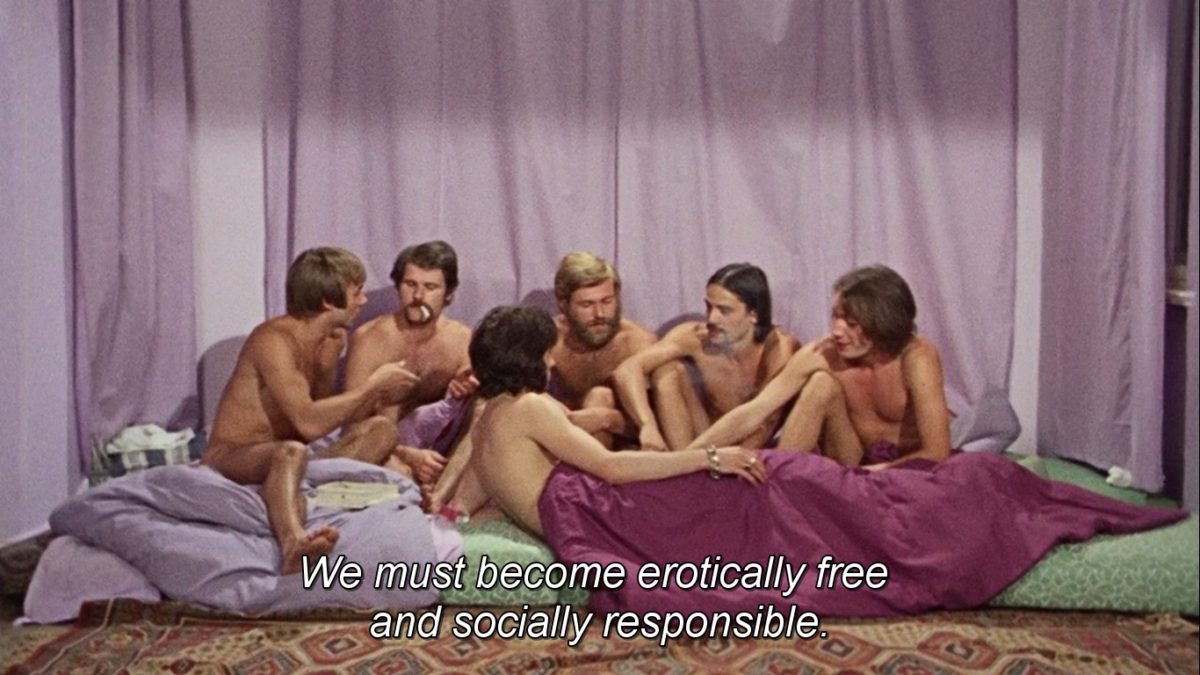

It’s the 26 of November and what is almost a normal day, an image becomes viral on my social media. In it, six naked bodies sit on top of green cushions. One of them lies across, back facing the camera, engaged in a conversation with three others, covered with a dark violet sheet. It looks like cotton, I think. Four of them, occupying the three-fourth right side of the frame, are engaged in a conversation, their faces seem relaxed, their bodies touch each other, unpreoccupied. Light purple sheets hang from the walls behind them, lightly waving and covering the cushions where another two bodies sit, immersed in their own discussion. One of them smokes a cigarette. Upon further inspection, they all reveal as men, or so it seems. At the bottom of the image, the further caption reads: “we must become erotically free and socially responsible”. This image belongs to the movie “It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives”, released on the 24th of November of 1977 in New York, originally released in Germany in 1971 and directed by Rosa von Praunheim.

The movie was deeply influential in Germany and elsewhere, politically organised action groups sprang across the country from 1971-1973, triggering the gay liberation movement (GLM) in the country. This quote is fascinating. It perfectly captures the ethical commitments that should inform the movement; the productive tensions between two seemingly irreconcilable political aims of the fight for sexual liberation that could not be achieved independently. This quote was undoubtedly generated by a clear and sharp political mind, definitely. But most importantly, it was the product of the political context which provided the tools for GLM, a political context that envisioned a society composed of mutually dependent individuals; a society in which identities were forged, reproduced, differentiated, rendered invisible as they were, intimately dependent on the form of the economic relations that mediated between them. From this perspective, sexual liberation would require a complete transformation of our society, which form is inseparable of the form in which property is organised: a society in which all systems of oppression and exploitation are interrelated, where all are embedded in their experience of oppression and where the same emancipatory aim is shared, a society where it is not possible to be individually free only, but also one must be collectively free. And freedom, this kind of freedom, can only be achieved if we look after each other, if we become responsible for each other, if our solidarity demands collective radical care, by all of us regardless of gender, race, sexuality, capabilities, age. A revolutionary political horizon and praxis.

Even more striking to me is that the movie was released ten years, five months and three days before the New York Times announced to the world what would become first known as the gay cancer, later identified as AIDS, produced by the HIV virus. This would become of public concern after several middle class white gay men who had access to private health care, therefore able to overcome the social and economic barriers distinguishing between valuable and invaluable deaths, provided enough scientific evidence, published in official medical documents, to raise concerns about the existence of a “new” deadly virus, forever binding the fate of the queer movements to the devastating consequences of AIDS. And of course, AIDS was already killing people in the US and elsewhere before it became portrayed and endlessly reproduced by media and governments as the gay diseases, conflating the heterogeneous multifaced and complex social composition of HIV positives and its manifestation in diverse symptoms as AIDS, into the homogeneous “body” of the “gay”, now reduced to a signifier directly related to the cis, predominantly white male homosexual, cemented by mechanisms of state power and public discourse.

It is sometime between the end of March and the beginning of April, in the middle of national lockdowns across Europe and elsewhere. My uncle dies of COVID in a hospital in Spain, while new cases break the records day after day. Well, he had been fighting a cancer that lived with him for over twenty years, he would have died sooner or later anyway, or so I tell myself to cope with the idea that he waited to die, alone in a bed in the library of an overcrowded hospital for three days since they stopped treating him for good and prepared him for his end, surrounded by others like him.

It is sometime mid-September, I think, although time has become increasingly hard to grasp, it could be any other time in the near past. Covid exists. Summer is coming to an end. My heart stops for a second at the sight of rainbow flags, too many of them, in an anti-lockdown, covid negationist, anti-vaccine and what not demonstration in Berlin. Categories mix.

It’s 28 of November. Finally, I find von Praunheim’s movie online, in Vimeo, and I set myself to watch it with my flatmate and a friend who lives alone, in Barcelona. He called me this afternoon to tell me he was struggling, needed help and felt sad and lonely. I tell him “let’s watch the film together”. He replies “like couples in a long-distance relationship, how cute”. Exactly, simple, spontaneous, like that bit of privatized care that only seems acceptable within the framework of whatever (wrongly named) “love” relationship you happened to have at that particular moment. –Just as a cautionary note before I move into the matter. Many of the movie’s critical points seem odd to us now, some ideas have been given a more complex analysis, detached from unquestionable and inherited hetero-patriarchal understandings of what matters politically. Nonetheless, there is something in particular that I find interesting— In the movie, we follow the life of the protagonist entering the gay world of Berlin, breaking from the constraints of a closeted life in rural Germany, now “free” in the city. Paradoxically, the movie talks about loneliness, and about the particular social position that the homosexual of early 1970s German society occupies. He looks for romantic love as he has been told to hope. However, unable to fit into the confines of the middle-class family structure built, according to the voice in the background, for heterosexual couples in an exchange of mutual interests, for the homosexual “this romantic and idolizing love is nothing but self-love”, authoritatively states the narrator while a blond masculine tall guy melancholically stares at a cabinet holding some books, some Elvis Presley’s vinyls and a porcelain dog resembling the impersonal domestic space of an unreachable middle-class family house with a touch of eerie mismatch, a sudden break of reality (I must confess that this scene is weird to me. I cannot relate to the feeling of longing for an unfulfilled middle-class existence the protagonist seems to feel. For many of us, that possibility is simply materially unavailable, out of scope, not even something we can long for or aspire to. It is only increasingly a possibility for a narrowing strata of our society).

A society where social relations other than marriage are mediated by the fuel of competition necessary to keep the economic engine of the capitalist mode of production running –so the narrator believes— forces homosexuals to seclude to themselves and to the satisfaction of their immediate needs sublimated in disposable relations of lust and desire, unable to develop any sense of care that must be forged in a mutual commitment and responsibility. This is an interesting point. Clearly inoculating some inflated conception of capitalism’s needs to make us competitive subjects in order to build towards his political rejection of the status quo of gay life in Berlin at the time, the narrator hints at something deeper, easily missed. He poses the question, where do gays learn how to care for each other, if everyone else does it through a form of contractual love reproduced through social institutions out of our reach? What comes first as freedom from social conservative relations such as normative marriages or traditional family structures turns into a form of paradoxically dystopian freedom in the absence of a model where these habits can be socialised and reproduced among gays. If gays exist outside the family, biological reproduction detaches from the institution of the family and becomes dependent on the market. But what about cultural reproduction? “For gays, freedom is not about taking responsibility, but chaos”, dictates a voice while a couple of faggots fight in the street to then reconcile in a hug of mutual love. Luckily, the narrator of the film was wrong. Or maybe the forces unleashed by the movie’s revolutionary message ensured that, at the moment in which it was most needed, queers knew how to look after each other. Watching the movie, I can’t help but think how many of the actors would still be alive now, maybe a question not many people have to make themselves ever.

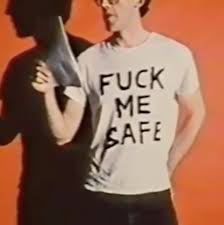

It is some time between the end of the 80s and the beginning of the 1990s, certainly before 22 July 1992, as that was the date when David added his name to the huge list of people who died of AIDS. Probably it was way earlier, as his mental and physical health strongly deteriorated from December 1991 until his death. In the picture, he stands, pursed lips, ready to throw the next line with the intensity and anger that characterised him in his public readings at ACT-UP events in New York. He holds a script with one hand, the other lying on his hip. On his white t-shirt, handwritten in black, you can read, FUCK ME SAFE. Among the many incredible actions of AIDS’ activists during the crisis, one of them was centred around the task of sex education. Instead of accepting the moralistic and hypocritical view of the government that called for sexual abstentionisms as the only mechanism to stop the spread of the virus, they promote the political importance of engaging in sexual acts that were safe. Teaching people how to use the condom was one of them, but breaking all the taboos and paranoia around HIV based on scientific evidence was a fundamental task to learn how to keep on living and understanding the risks of our own actions. To keep yourself safe and everyone else safe, and remain free. However, they did not accept their position as doing the job for the state and simultaneously demanded that effective treatments were developed, that social security and access to health care was provided for everyone regardless of their material conditions and serological state, that those who could not work because of the advance state of their illness would have their needs satisfied by the state, that law must be changed to protect people, that the reality of the issue should be faced. A Majority Action Committee was created to address the ways in which poverty and racism shaped the dimensions of the crisis, a name that was conceived from the fact that, at that moment, the majority of people dying of AIDS were people of colour. Exchange used needles between IV drug users was one of the main paths of transmission of HIV, together with unprotected sex. Needle possession was illegal, they acted, they changed it. “If not using a condom can contribute to the spread of AIDS, then distribute condoms. If sharing needles can contribute to the spread of AIDS, then we need to distribute needles”, says Dan Keith Williams, ACT-UP activist, in an interview with Sarah Schulman for the ACT-UP oral history project. ACT-UP activist did challenge the universalisation of AIDS symptoms as the ones officially accepted were only focused on those developed by white, cis, gay males, a problem that was resulting in many none-males, non-white or IV drug users being discarded from the already thin system of social security that had been granted to gay male AIDS patients. On January 22, 1991, two ACT-UP activists interrupted a live transmission of CBS News evening shouting “AIDS is news, Fight AIDS, not Arabs!”. A strong internationalist anti-war position that wanted to unmask the hypocrisy of a government that declined to take responsibility for the lives of their citizens with proper investment in health and social security while simultaneously starting a war in the Persian Gulf. One day later, they occupied the hall on Grand Central Terminal, where they hung banners with the messages ”Money for AIDS, not for war” and “One AIDS death every 8 minutes.”. They call this the Day of Desperation. And by the way, all their activism was only possible thanks to the political tactics and ideas developed by central American solidarity and the anti-nuclear movement of which many activists were part. It was also the result of the political experiences developed by feminist activists that could be mobilised thanks to the activation of forms of solidarity between gays and lesbians that had paradoxically become possible as a result of the obfuscation of the lesbian as opposed to the male homosexual in the all-encompassing term “gay”. As Chitty writes, “Feminist affinity with male homosexuality often involved solidarity with gender-variant types and with oppressed axes of class, racial, and sexual identity from which the mainstream movement for gay rights sought to distance itself” (Christopher Chitty. Sexual Hegemony; p 146). It was everything but a single-issue movement. There was nothing such as an innate, essential, external, “queer form of knowledge” that produced this political response, but the result of a historically contingent socio-political moment, a chain reaction that rapidly exceeded and became totally irreducible to the chemical characteristics of its primary reactive catalysed by the materially interrelated solvent of the moral, political, social and care crisis of AIDS. Silence = death would become the most powerful and mediatic statement of ACT-UP. This simple sentence, I believe, acquires its full meaning when read as the mirror image of another equation that sparked the fires of the GLM, care = freedom, a mathematical and stylistic representation of Rosa von Praunheim’s viral caption: we must be erotically free and sexually responsible.

I believe that there are important lessons to learn from these experiences. They can help us to deal with the present crisis and the future of the movement and our society at large. What are the equations that define the politics of the present? what do we see, hear, create? what is the role of care, or which kind of “care” is being mobilised, and to which effect? Only when the constructive tension between these two aspects of life (Care-Freedom) is lost, can the lockdown measures, or the imposition of a face-covering mask be perceived as a completely unacceptable attack on our individual freedom. In a context where all of us are forced to experiences ourselves as autonomous individuals, relations of care can only be understood as a burden on top of the already exhausting and necessary task of self-reproduction, an individualised duty from which one can decide not to engaged and retreat, either by don’t giving a fuck about others altogether or behind the politically inflated but clearly dubious discourse of scented candles and lush baths of self-care. But there is not such a thing as self-reproduction but social reproduction. Only one form of care that emanates so strong, that mediates so strong that bridges us all together and illuminates the contours of the future social order to come, one that can empower us to fight for this future, only this form of care is revolutionary care. Revolutionary care is not opposed to freedom but becomes freedom’s equal. But how does this care looks like? Where does it come from? How does it feel?

——————————————————————————————————–

Like many, David witnessed the death of friends after friends, caring for their disintegrating bodies (literally) while families remained either unaware or too ashamed to publicly confront the fact that the blood of their blood was immorally dying of a socially and politically rejected disease, privately ostracized. David took the photograph of his best friend and former lover Peter Hujar seconds after he died in the hospital, while he was sitting at his feet, immortalizing for as long as humanity will remain in this nearly mortally ill planet the life and experience of a whole generation all over the world. He would take him to experimental clinics with opportunistic doctors who would try to make history by testing all ways of new unofficial treatments, many times with little scientific evidence, a venue that only the desperate would accept as a last line of hope when very few options were available.

In an undated entry on his diary, in 1988, David wrote:

“So I came down with a case of shingles and it’s scary. I don’t even want to write about it. I don’t want to think of death or virus or illness and that sense of removal that aloneness in illness with everyone as witness of your silent decline that can only be the worst part aside from making oneself accept the burden of making acceptance with the idea of departure of dying of becoming dead. Ant food, as Kiki would say, or fly food, and it is lovely the idea of feeding things after death but no, that’s not the problem –the ceasing to exist in physical motion or conception. One can’t effect things in one’s death other than momentarily…In death one can’t be vocal or witness time and motion and physical events with breath, one can’t make change. Abstract ideas of energy dispersing, some ethical ocean crawls through a funnel of stars, outlines of the body, energy on the shape of a body, a vehicle then extending losing boundaries separating expanding into everything. Into nothingness. It’s just a can’t paint. I can’t loosen this gesture if I’m dead” (David Wojnarowicz, In the Shadow of the American Dream. The diaries of David Wojnarowicz; p 211)

It wasn’t death that he feared, it was the incapability to produce change through action, something he desperately tried to achieve through his art as a form of activism. “I showed him much of my work and his response has been one of disinterest or at least of being mostly unaffected by my images”, he wrote in his diary, September 21 1981, before the AIDS epidemic kicked in. “I left his place and met later with Jesse and Brian, feeling a lot of anger at the state of my own art, feeling that I’m stuck in some sort of limbo with my work, feeling unencouraged, feeling that I will never get anywhere with my stuff, as if it is quite meaningless to the people I most want it to have meaning for, feeling that as an artist or person who creates, that I’m basically a failure, that I haven’t reached a sort of state that lets creative action something that has an independent meaning or is capable of affecting change in anyone other than my friends. What does this mean? I simultaneously see the absurdity of this, why would I want to effect change, isn’t that an impossible desire, isn’t change through action? Work, an impossible thing to ask. What is it that I want to change? Maybe I want people to faint at the meaning of my work. What would that be like, fainting through something not like fear or challenge but through a sense of it being so true in this world as an independent existence? This is something I don’t think is possible to define”. Effect changed in a deeply sick system, the truth of the possibility of another world dissolving just at the verge of its representation under the weight of a true immediate reality imposed upon him by what he defined as the “Other World. The other world is where I sometimes lose my footing. In its calendar turnings, in this preinvented existence…A place where by virtue of having been born centuries late one is denied access to earth or space, choice or movement. The brought-up world; the owned world. The world of coded sounds: the world of language, the world of lies. The packed world; the world of speed in metallic motion. The Other world where I’ve always felt like an alien. But there’s the world where one adapts and stretches the boundaries of the Other World through keys of the imagination” And when one feels that he is about to break from reality…“But then again, the imagination is encoded with the invented information of the Other World. One stops before a light that turns from green to red and one grows centuries old in that moment”. It is that Other World which is different from the world, but so present and dense that thinking of an alternative becomes impossible. It is the self-imposed Real that challenges any alternative as utopian. An impossible thought and representation.

An impossibility of representation that he would later try to defeat: “breaking silence about an experience can break the chains of the code of silence. Describing the once indescribable can dismantle the power of taboo to speak about the once unspeakable can make the INVISIBLE if repeated often enough in clear and loud tones…BOTTOM LINE, IF PEOPLE DON’T SAY WHAT THEY BELIEVE, THOSE IDEAS AND FEELINGS GET LOST. IF THEY ARE LOST OFTEN ENOUGH, THOSE IDEAS AND FEELINGS NEVER RETURN.”

It’s 28th of November. I am meeting a comrade in Finsbury Park for a one-to-one walk along Parkland Walk. Probably the only social interaction away from the household bubble where the risk of transmission of COVID is sufficiently low, as corroborated by the latest scientific studies available. I bike there, a 40 min ride through rapidly changing boroughs, thinking how travelling in London seems to me like moving from one city to another at the cross of every four roads, and how difficult it is to conceive a radical municipal movement when the lives of the people seem to be drastically unconnected in such a wide span of houses and bricks and high streets and Sainsbury’s and local gyms. We are meeting to discuss what it means to be a revolutionary organisation today. An experiment, as well, to start building back connection, with a growing feeling of isolation amidst this pandemic expressed by some. Those who do not want to meet face to face can speak on the phone or write a post. What matter is that we connect, talk, discuss, think together, try to move together away from the political now. Walking between people jogging or jumping with the skipping rope we talk, the path backed between graffiti walls and greenery. “The aim of a revolutionary organisation should be that of building a shared emancipatory horizon around the already existing political struggles”, “to connect, to offer a network”, “people already have very radical ideas”, “we don’t want to be vanguards, of course”, “Before squatting became criminalized in the UK, there were more than X thousand (I do not remember the exact number, but I do remember it struke me as remarkably high) only in London, can you imagine?”, “This is crazy for me. I cannot conceive of something else than this very thick and all-embracing capitalist social relations that I feel so present in London. I can’t simply think of the possibility that this ever existed, in the recent history of the UK, which is crazy”, “it did”…“We need to believe the fact that most of the people already want a change from this fuck up system”. We both agree, we part ways.

It’s some time between May and June. I’m in Spain, where I moved to help my mother who has taken upon herself the responsibility of taking care of my grandmother alone. The results from the blood test come back, the diagnosis is not good. They confirmed my mother has a yet unidentified autoimmune disease, the constant pains she lives in will likely increase as she ages, but I can’t even think about it. We can’t even think about it. My mother puts the results back in the envelope and we don’t talk about it for months. How will we hold this together? At the beginning of the lockdown, she had to close the bakery where she was working for as long as I can remember. She could not afford to take the risk of carrying the virus to my grandmother, with whom she lives. Paradoxically, all my family fell sick the second week of lockdown, of COVID. They survived, but she won’t open the bakery again. A bakery where my grandmother worked before her, and my grand-grandmother before them, a whole legacy of bread makers precedes me. She would go there every single day of the year, resting only 15 days in the summer, the 25th of December and the 1st of January. Bread is a first necessity, an indispensable item in people’s diet, I cannot simply close, this is the service I provide to this town and people will be angry at me. That is what I always heard growing up, my mother repeating the words of my grandmother. Workers work, that’s it. Later, talking to my father, he shows me an excel file where he keeps the count of the days left before he can retire, six years and something, he counts it on working days, but I don’t remember the number. “I’m sick of this job, all I need to do is to keep a bit more, just a bit more, and then…fuck them!”, he says to me. “I hope they find the vaccine and make lots of money, so they will not fire me”, “I think it doesn’t work like that, dad”, I tell him, he knows. For the last 30 years he worked in the IT department of the pharmaceutical company GSK, previously SB, and now another name I don’t remember after some merger I lost count of. In the last twenty years, they have been externalising his department and all I can remember is him coming back home telling me about other colleagues being fired one by one, him waiting the moment at any time soon. In a conversation we had during this long lockdown that forced us to come back together again, he even confessed to me that he smoked hash every day to endure the fact that he hated going to work, to deal with it, with that reality, a fact that partially explained why he was so absent. A couple of months after this conversation he was fired, thirty years working on a company that is as his and as of any other worker as it is of any other investor, or manager or whoever the fuck is at the “top”. Put in the street in the middle of a world crisis. GSK, like many other pharmaceutical companies, has enormously profited from this “crisis” and will continue doing so. All they needed was a good financial year to get rid of those expensive surplus workers still protected by old workers’ rights with high compensations. Off you go, thanks for working with us.

This all seems to me to be connected, somehow. “Ever since my teenage years, I’ve experienced the sensation of seeing myself from miles above the earth, as if from the clouds. I see the tiny human form of myself from overhead either sitting or moving through this clockwork of civilization…And with the appearance of AIDS and the subsequent deaths of friends and neighbours, I have the recurring sensation of seeing the streets and radius of blocks from miles above, only now instead of focusing on just the form of myself in the midst of this Other World I see everyone and everything at once. It’s like pressing one’s eyes to a small crevice in the earth from which streams of ants utter from the shadows –and now it all looks amazing instead of just deathly”.( David Wojnarowip – Closer to the knives, p. 97)

Is this like a representation of an interconnected society breaking through this mess? The very possibility of revolutionary politics?

——————————————————————————————————–

It’s 6 of January 2020. I write in my diary that I am in love with David Wojnarowicz. It’s a transhistorical form of solidarity that breaks the constraints of space and time and expands backwards and forwards and across borders and nations, forms of life and death. A form of radical love that we must aspire to with every living and non-living entity, and I consider the earth and the universe as a deeply complex living ecosystem. Is this communist love?

Von Praunheim’s gives a radical turn to the movie as its end approaches. After inoculating the audience with direct messages of intense social alienation, with the supposedly inherent apolitical character of the male homosexual and with different common sense superficial understandings of homosexuals here and there, the protagonist gets invited to a sort of alternative commune to chill with other guys, away from the bars and toilets where he usually cruises for some anonymous and uncommitted shag. This is the scene from which the viral image was taken. “I’m afraid to fall in love. Time makes one cautious. I’m pretty lonely actually”, says the protagonist. “You have become incapable of having human relationships. Everything is cold, calculating and uptight”, they tell him.

All that comes from here is a long conversation where the members of the commune state the facts and potential political solutions. “we don’t want to stay together out of compulsion, but of our own free will. It may be more difficult, but at least it’s honest. Two guys who isolate themselves from everyone else, only to live for themselves, are being egotistical and cruel towards others. We need to live together and not against each other like in a marriage.” If homosexuals have been expelled from the structures where care is socially accepted and constrained, why not turn it outwards, towards every existing form, instead of onwards in a deeply superficial and narcissistic way, as a pathology of a perverse society. Then the viral caption comes, and the whole of the conversation that follows that line, a part that seems to be missing in the viral reproduction of catchy half processed slogans, just because maybe sexual freedom in itself is what sells the most: “sex should not be a competition or a way to boost your ego. It should contribute to understanding and not, as is often the case with gays, make them strangers after a one-night stand. We must try to fuck freely and respect the other instead of seeing him as an object. We must become erotically free and socially responsible. Let’s unite with the Black Panthers and the Women’s Liberation and fight the oppression of minorities! Take care of each other’s problems at work! Show your solidarity if a colleague gets into a conflict, and you can count on their help in return. Engage in politics! Being gay is not a movie! We gay pigs want to become humans and be treated as such! We have to fight for it! We want to be accepted, and not just tolerated. But it’s not just about being accepted by the people, but also about how to treat each other. We don’t want any anonymous groups! We want a joint action, so we can get to know each other while fighting our problems and learn to love each other! We need to organize! We need better bars, good doctors, and a safe working environment! Become proud of your homosexuality! Get out of the toilets! Take to the streets! Freedom for gays!” And then, the movie ends, with this brilliant proclamation of free love as an ever-expanding sense of solidarity. Love unbound. Truly revolutionary love. Truly revolutionary care.

The more I look back the more I understand the complex intricacies of AIDS and queer politics. Terre Thaelmitz, ACT-UP NY activist, illuminated me this time. As they write in their blog, “Today, most people see same-sex marriage as an ethical debate about the right to publicly express one’s love for whomever they choose. In fact, it is an ongoing struggle for access to social privileges. While the same-sex marriage movement has a long history, its current visibility is largely the result of HIV/AIDS activism in the US during the ’90s. Accepting the cultural impossibility of socialized health care, energies were desperately redirected to spousal rights as a stopgap solution for quickly expanding the number of insured gay men. In addition to spousal health coverage, legal recognition of same-sex marriages would grant partners family visiting rights in hospitals, the ability to make health care decisions when a partner is incapacitated, the right to remain living in an apartment leased under a partner’s name after their death, shared child custody rights, and a wide variety of other privileges.” (Thaemlitz, Deproduction). It was a matter of deciding what was pragmatically useful in a moment of crisis that determined a big part of what became one of the central battles of LGBTQ movements across the world. But they were not the only ones who saw marriage and the fostering of same-sex family structures as the good solution for the crisis, if for completely different reasons. In the most contemporary context, Richard Posner And Tomas Philipson, two Chicago boys, argued in 1993 for the regulation of same-sex marriage as a neoliberal reform to deviate individuals’ claim to universal healthcare and welfare provision into the privatised form of the family support network, the social insurance function of family and marriage. The ethics of family responsibility as opposed to the more encompassing ethics of social responsibility from which the state cannot retract itself. “If AIDS was the price to pay for an irresponsible lifestyle choice, same-sex marriage is now presented as the route to personal (and hence familial) responsibility” [ Melinda Cooper, Family Values, p 214]. Yes, same-sex marriage is a fundamental achievement for equality, and as of today, still, a very useful mechanism to grant access to particular provisions and benefits in many familiarist welfare systems. But that is a necessity materially inscribed in the political and social order, and we are here to think about the realm beyond necessity as a real possibility, so let’s fucking interrogate this. However, I do not intend to tell a story about the positive or negative aspects of same-sex marriage. This is neither an attempt to infuse queer desire and bonding with any form of potential subversive power, as if resisting the family should be placed in a lost radical pre-existence that, from a historical perspective, has never been there as a given. (A small remark: the respectability of the family structure and its role against the “social degeneration” and “moral decay” in which not only homosexuality but proletarianised social forms lived has been endorsed by different political actors across the spectrum since the XIX century, with devastating effects for the true liberation of gender and sexuality and with amazing advances for the working class as a whole. It is just that history is messy, difficult, dialectical, what can we do? Importantly, as well, when we talk about the family form and role in the capitalist social relations, we need to understand how this institution has been shaped historically as political, social and economic events unfolded, and the history of gay politics and social organisations “in” and “out” of the family institution has been shaped by these forces accordingly (see EndnotesTo Abolish the Family)). So instead of thinking through unhelpful false polarities, I rather use the particular historical development of the politicization of homosexuality as an interesting vantage point from which to enter into the further economic and political interests behind the material and discursive reinforcement of the institution of the nuclear family. This is a particularly illuminating vantage point as the homosexuals, favoured by the developments of capitalism and the loosening of the economic function of the family, were put into a position from where a particular subjectivity was produced, and our introduction on the more or less hegemonic family structure was the result of political and economic forces difficult to subsume into the “natural” inherited social institution of the family. What matters, I think, is to consider the possibility that the “privatization” of care into the realm of the family produces a hierarchy on which we place grades of burden, from individual to family to extended family to our “community”, preventing us to build an all-encompassing solidarity in which our relations are nurtured, where everyone’s well being is part of our responsibility, just as neoliberals hoped, regardless of sexuality.

Posner and Philipson’s suggestions, which strongly problematizes dubious understandings of homophobia vs toleration as the sole result of cultural representation and acceptability in western societies, are not the result of a more “progressive” neoliberal thinking. The institution of the family, which form can be extended from the strictly nuclear family to kin-based organisations accordingly, is defined as a network that organised social care responsibilities across familial bonds that are then subtracted from society as a whole, or as a privatised system of household base social reproduction in the couple form, which privileges genetically centric kinship, to quote comrade Kathi Weeks, or as a bound of all different sources of personal relationships that mediate access to the wage for those unable to access it for a period of time, quoting comrade ME O’Brien (see Red May talk, Abolish the Family!, Youtube). This particular role of the institution of the family had been a matter of preoccupation for early conservative neoliberals alike, in the context of a perceived dissolution of traditional social relations that worked to reinscribe as natural what were specific, historically contingent class relations.

Writing in 1921, Alexandra Kollontai, a revolutionary, attempted to develop the moral contours of a society where the family unit had ceased to function as an economic unit and had therefore become obsolete in a communist society. In this new economic order, new social relations would emerge in place of those previously mediated by private property ownership. These would mean completely new ways of love and sexual relations, ones now informed and mediated by “mutual respect, love, infatuation or passion”, where “jealous and proprietary attitude to the person loved must be replaced by a comradely understanding of the other and an acceptance of his or her freedom”, sexual relations in which “the bonds between the members of the collective must be strengthened. The encouragement of the intellectual and political interest of the younger generation assists the development of healthy and bright emotions in love” (Alexandra Kollontai, Selected Writing; p. 231) She envisioned the project of the abolition of the family as strictly necessary if real solidarity among the collective was to be developed in a society. Thus, she wrote:

“In view of the need to encourage the development and growth of feelings of solidarity and to strengthen the bonds of the work collective, it should above all be established that the isolation of the “couple” as a special unit does not answer the interest of communism. Communist morality requires the education of the working class in comradeship and the fusion of the hearts and minds of the separate members of this collective. The needs and interests of the individual must be subordinated to the interests and aims of the collective. On the one hand, therefore, the bonds of family and marriage must be weakened, and on the other men and women need to be educated in solidarity and the subordination of the will of the individual to the will of the collective.“

Any would naturally feel aversion for the strong wording Kollontai uses when demanding the subordination of the individual in the collective. However, a disagreement on this, even if reading it on its historical context would show this conclusion more a matter of contingent political strategies than essential unsurpassable theoretical commitments, should not prevent us from addressing the core of the matter: the consolidation of new society once private property has been abolished. A social order that replaces one made up of atomised individuals, forced to mediate most of their anonymous interactions by economic interest and material self-preservation.

The interwar period in which Kollontai made her contributions from the social state of the soviet union as the only women to be part of the government after the revolution was one marked by a feeling of an intense search for new social bonds that could challenge the rising power of class solidarity effectively articulated by labour movements across Europe. In the Weimar Republic, for instance, an intense phase of associationism provided the social hummus for the politicization of social relations and for the exploration of their new potential, sometimes articulated against the “illegitimate” order of the Republic, against the “irrational” order of the proletariat, and/or against abstract powers that were deemed responsible of the atomisation and isolation of the social order they thought to be challenging. The idea that same-sex attraction between males would provide with the necessary cohesive bounds was received with enthusiasm when Hans Blüher, a representative of the far-right revolutionary conservative creed of interwar Germany and representative of the youth leagues movements, published his two-volume work The Role of Erotics in the Male Society. He thought that male homosexual desire was an asset, as it detached the individual from the task of procreation, thus freeing him from the constrainings of the family and biological reproduction and allowing his desire towards men to be sufficiently detached from material concerns as to crystalised a homogeneous and a cohesive social order, only if socialised by the Männerbund instead. This is the reason why he thought that the form of the young league should be promoted as the main institution for the socialisation of men and the cultural reproduction of the nation, as opposed to the family which existence, however, was taken for granted as a necessary form of biological reproduction. It goes without saying that it was an anti-feminist, arch-conservative project of national rejuvenation.

He, and other conservatives of this time, were not the only ones concerned with this matter. Contrary to the general understanding of neoliberalism as a project of individualisation, early neoliberals were deeply concerned with the transformation of the social bond in ways that would become harmless for the perpetuation of the free-market, if not directly beneficial, with social institutions where a capitalist morality invested in the preservation of this economic and social order would be reinforced. That was particularly the case for Wilhelm Röpke, who, together with other german ordoliberals, would participate in the creation of the Social Market Economy of post-WWII Germany. Röpke would become very influential in American neoconservative circles as well. He saw the dissolution of the family, by which he meant the heterosexual middle-class nuclear family anchored in traditional communities with shared values, as the main instigator of the social disorder they aimed to solve with their neoliberal policies. He saw this as the result of industrialisation, a process that had created working-class enclaves in cities where new social relations were proliferating, unrooted and easily persuaded into a working-class culture with potential revolutionary power. From his perspective, the task of social reproduction, which the welfare state was increasingly taking care of, should again be privatized in the institution of the family. This was the same logic that Posner and Philipson later employed when trying to deal with the growing “burden” of a state that demanded to be responsible for its dying population amidst the AIDS crisis. That of substructing care from society, to privatize it somehow. That of making the idea of society harder to be conceived. It is also the same logic, but inverted, that animated Kollontai’s arguments against the nuclear family if a communist society was to be maintained.

In the concluding paragraph of her essay, Kollontai writes:

“The stronger the collective, the more firmly established becomes the communist way of life. The closer the emotional ties between the members of the community, the less the need to seek a refuge from loneliness in marriage. Under communism the blind strength of matter is subjugated to the will of the strongly welded and thus unprecedentedly powerful workers’ collective. The individual has the opportunity to develop intellectually and emotionally as never before. In this collective, new forms of relationships are maturing and the concept of love is extended and expanded.”

I guess the question remains, is radical care possible within the current socio-economic order? Are freedom and care possible without questioning the structures of the family? The dimensions of this problem have come full-fledged during the current crisis, where the networks of support from the family have been stretched to its limits when available, if not taken at faith value altogether, almost becoming a charity to fill the gaps of an unwilling state (and let’s be honest, even for many families this is not a sustainable solution, not to talk about domestic violence and a push back to the relations of dependency and domination that queer and feminist activist have been fighting against for just too long now). Alternatively, others built their extended “families” in so-called support bubbles. Don’t get me wrong, we all need to survive in a ruthless system of private means of production, especially those for which the means to survive have been severed from them (yes, I talk about us “proletarians”, those of us dependent on the market and its forces placed outside of our direct control); these are all honest signs of love and support in an extraordinary and difficult situation, in a fucked up system. The solution, however, doesn’t address the problem. It simply extends or redefines the contours of who are deemed of our care and consideration and who are outside its reach. This has different political consequences. On the one hand, it prevents us from forging strong relations of solidarity where hierarchies of love and care are flattened, comrades outside these structures sometimes forgotten at hard times. Care becomes an afterthought instead of an ethos, a way of life, a political commitment. It always remains as something extra, on-top-of kind-of-thing. I know it is unrealistic to pretend that it’s possible to develop a conception of love and care that expands towards all existing matter without differentiation, and as a matter of fact, it is something pragmatically impossible in the present, if maybe for different reasons such as the pre-existing inequalities that demand us to prioritise where our energies are directed. But why not have it as a horizon? as a commitment? why not try to explore, being mindful of the fact that for the moment, this is an adulterated form of unbound love in the process. And to be honest, this is not even such an exercise of utopian science fiction thinking. Many of us are already forced out of the nuclear family structure or have never been part of one really, with the only possibility of sharing houses with friends or strangers. A whole generation coming-of-age in the post-2008 financial crisis has been jumping from one fixed-term contract into another ever since, while the housing market is rocketed once again by financial investors that seek to make profit, unscrupulous keeping empty apartments waiting for the price to rise, and kicking tenants with silent evictions in the form of sudden rent rises. The city becomes a huge machine of speculation that drains the pockets of its citizens, a luxury (the sacred realm of private property, or as one Spanish politician recently put it when rejecting to implement the rent-cap they promised in their manifesto: “a human right, but also commodity”, so commodity wins and FUCK YOU). And in this context, out of necessity, many of us learn how to live with others, accepting that this is not just a phase, something we do when we are in our 20s and life seems like a funny crazy LSD trip and instability could be cool because it keeps you busy looking for your true self, whatever that means, waiting to find the love of our life and move out together and form a family and be happy forever or maybe just don’t worry about it at all. But let’s face it, this is not a phase, this is how things are right now and how they will be unless we do something, and we can try to moor the melancholic seas of lost “stability” and “comfort” of a historically contingent social institution or we can start building from what we already have. The potentialities also point towards the present limitations, the most important one is that imposed by the sanctity of private property that so fundamentally articulates the capitalist order and the social relations within it. In the meantime, it seems to me that as long as these options remain unquestioned, the possibility of mass collective opposition to the heartless disregard of government to the wellbeing of ALL of us (just think of the rejection to keep school meals for kids of families on lower-income, one of the latest most popular outrageous positions) is trumped just at the moment when we need to move one step further, one living entity beyond. What is left is some sort of privatized network of community-based support that becomes vital for many, but won’t have the capacity to influence the process that generates its need. Putting a mask becomes a devastating task if you are not visiting your parents. The roll-out of vaccines are giving us some much-needed breath after a hard tedious time, but the conditions that generated the complex crisis that signifies COVID will remain unchanged unless we challenge them.

This society, even if pessimistic readings of some totalizing (neo)Marxist are right and the capitalist social relations of production have expanded to conquer even the last of our neurological paths to mould them at its cast, already contains in one form or another the seeds that are the conditions of possibility for a future different social, political and economic order. All we have to do is find them, water them, nurture them, stir them towards an exit or a rupture, take radical political care of them. Show the material limits and push to break them. There is only one way out and that way is forward.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

“I wake up every morning in this killing machine called America and I’m carrying this rage like blood filled egg and there’s a thin line between the inside and the outside a thin line between thought and action and that line is simply made up of blood and muscle and bone“ – David Wojnarovicz, Do not Doubt the Dangerousness of the 12-inch-tall Politician

“If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath my palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain.” – David Wojnarowicz, No Alternative.