By Gareth Brown and David Harvie. Cover photo credit: Jacob.

On the move

UCU (University and College Union) is on the move. Less than six years ago, our union’s national leadership was ordering 2-hour strikes. A handful of lecturers plus assorted librarians, technicians, and others stood shivering on the perimeters of campuses in what appeared little more than a long lunch break. The experience was not only utterly demoralising – because, of course, hardly anyone noticed – for many it also became humiliating and materially damaging when our employers decided to deduct an entire day’s pay for each 2-hour ‘stoppage’. The union proved helpless to prevent or reverse such ‘unlawful’ deductions.

But in February and March 2018, 42,000 members of UCU – academics, researchers and their professional services colleagues – took 14 days of strike action over a four-week period. It was the longest strike in UK higher-education history and disrupted 64 universities. According to the ONS, Britain’s statistics agency, only 273,000 working days were lost in 2018 as a result of labour disputes – the sixth-lowest annual total since records began in 1891 – but two-thirds of these working days were lost in the education sector, mainly universities. UCU members struck again late in 2019, with eight days of continuous strike action at 60 institutions. A further 14 days of strikes will begin on February 20, involving 74 universities.

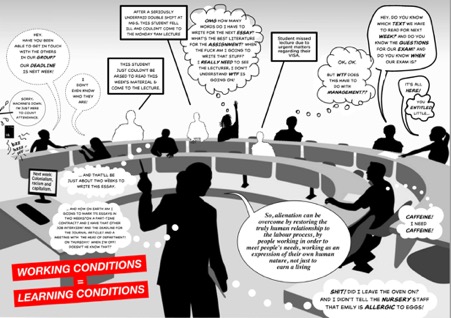

The education sector in the UK is a frontier of capitalist development, a frontline of struggle. In universities metrics, rankings and league tables have become ubiquitous. Students are encouraged to see themselves – and behave – as consumers. Bosses – usually known as vice-chancellors or VCs – are making increasing use of precariously-employed workers for both teaching and research; they are increasing workloads for everyone. Poor physical and mental health are the inevitable result. The university has become an ‘anxiety machine’.

But capital has been exploring this frontier for several decades now. Marxist and other critical scholars have been writing about the ‘global entrepreneurialisation of the universities’, ‘academic capitalism’ and the ‘proletarianisation’ of academics for at least a quarter of a century. Why has our resistance only seriously erupted in the past couple of years?

We’re not entirely sure why anger that had been simmering for years only ignited in 2018. One possible reason is that 2018’s strike was the first involving young workers who’d come up through the UK’s student movement of 2010. Eight years later, they’d graduated, probably done some post-graduation education and were old (and qualified) enough to have waged jobs in universities. They brought their experiences of student militancy with them.

A second – complementary – reason is that British universities are far more international than they were a couple of decades ago. Migrant workers carry with them experiences of political and workplace struggle from other places: such diversity can obviously only enrich movements, but in particular, struggles in other countries have frequently been more militant than those in Britain. In both 2018 and 2019, migrant comrades frequently remarked on the hesitancy, caution and conservatism of British workplace struggle; at University of Leicester (where both the authors of this article work) in 2018 it became a running joke that one necessary ingredient for a successful strike was the involvement of Italian militants.

A third possible reason – which again complements the first two – is simply that there is a tolerance threshold. Post-2008, life has become harder for almost everyone. In universities – and many other sectors, it’s true – the squeeze on incomes has been coupled with increased stress that comes both with work-intensification and with insecurity. It took a decade, but eventually we reached the ‘enough is enough’ point.

‘This kind of feeling could move a nation’

Going on strike can be a powerful affective experience. A ‘bad strike’ – those 2-hour strikes in 2014, for instance – demoralises, makes you feel weak and powerless. You feel you have less capacity to act. It’s visceral: you don’t want to be on that picket line, you don’t want people to see you there, you feel like you need to make yourself as physically small as possible. This is why people who participated in those strikes said it was embarrassing: we literally felt ashamed.

A ‘good strike’, by contrast, produces the opposite affect. It gives you a sense of collective power, a feeling that your ability to act and to change the world is expanded. It’s a powerful feeling – a ‘moment of excess’. We – us two and we think many others in Leicester – experienced such emotions in February–March 2018 and again in November–December 2019. It’s a feeling we last experienced during counter-globalisation mobilisations against the G8 a decade and a half ago or, even further back, Earth First! actions. That sense of anticipation, urgency and excitement when you stumble out of bed in the small hours and head out into the iron light of dawn.

This affective power of the strike was unevenly distributed, however. At 90-odd institutions an insufficient number of UCU members voted. (According to the Trade Union Act 2016 industrial action is only lawful if ballot turnout is 50% or greater.) And even at universities where UCU members officially took strike action, not all union members (let alone all employees) actually observed the strike.[1] We suspect that some institutions were able to carry on business pretty much as usual. The picture is further complicated by the fact that even when lecturers and seminars went ahead ‘as normal’ (because lecturers were scabbing), these were often extremely poorly attended: lots of students actively supported the strikes and would not cross pickets lines; the general hype surrounding the strikes meant many students simply assumed there’d be no teaching going on; some students no doubt decided that claiming to have assumed a lecture was cancelled would be a good excuse if they got into trouble for poor attendance.

At some institutions the strikes were relatively solid, with most teaching events and meetings cancelled, but strike activities themselves were muted. For example, some UCU branches took the decision to remain off-campus at all times. In our opinion, this was a mistake. It creates minor absurdities of picketers struggling to find toilets – whilst only metres from buildings containing many such conveniences, but inconveniently on the wrong side of the picket line. More generally it concedes the university, its space, its resources, its wealth, to bosses.

In Leicester, by contrast, we marched onto and around the campus every day of our strikes – with chants and full band – always ending up for songs, speeches and other planned or impromptu performances in front of the main administration building, what was once the Leicestershire & Rutland Lunatic Asylum. This on-campus activity disrupted the university’s day-to-day running, including those lectures and classes that weren’t cancelled. It also contained a powerful message and reminder, for us and for our bosses: the university is ours!

There might be trouble ahead

So there has been a small explosion of militancy on British university campuses. We do not believe the energy unlocked in this explosion will quickly dissipate. But nor do we think it will scale up much further without a broader cultural shift. As we suggested above, the strikes’ power – both affective and more material – was unevenly distributed. We have to be honest and recognise that scabbing was probably widespread. We also have to recognise that not everyone who scabbed was necessarily being selfishly individual – or individualistically selfish. One task of campus militants is to attempt to stimulate the cultural shift that means that not crossing a picket line, whether physical or virtual, becomes second nature to most workers.

One reason education workers are averse to go on strike is because they/we are typically reluctant to harm ‘their’ students. This both suggests another reason why latent discontent exploded in 2018 and presents a challenge to militants.

First, the reason for more militant action in 2018 and 2019. University bosses’ use of a casualised workforce – perhaps half of all teaching is done by precariously-employed workers – means that many UCU members no longer have students they think of as ‘theirs’. This sense is reinforced by the market narrative that students are, in fact, customers – a reframing embraced by bosses and some students. The result is that today’s typical university teacher feels a very different sense of responsibility towards students than that of an academic of two decades ago. Moreover, it’s become clearer than ever that, in the casualised classroom of the neoliberal university, there are now many factors harmful to students’ education and that a teacher’s absence due to strike action is but a bagatelle.

Second, the challenge. Many university workers – certainly most academics and researchers (perhaps less so ‘professional services’ employees) – are philosophers: we are lovers of wisdom. We got jobs in universities because we wanted to pursue research and to share this research with others.[2] When we strike we stop doing research and we stop teaching. That is, we stop doing what we want to do; we stop engaging with the people (students and our scholar peers) that we want to engage with. This dilemma is not unique to us. It’s one faced by workers in caring jobs – junior doctors, for example. How can we strike against – cause damage to – our employer, without harming students or patients or passengers or whatever?

Many university strikers put their scholarly energies into teach-outs and the production of strike analysis and materials. A key feature of this activity was that it was self-directed: no external power was imposing curricula, ‘assuring quality’ or attempting to measure student ‘satisfaction’ or ‘experience’. So, in this sense, strikers continued doing what they like to do or, better, since it was self-directed, they gained to space to do more of what they like to do. We know of many scholars who participated in few overt strike activities, but nevertheless turned off their university emails and spent the time sitting at home, lost in their books – an activity which few of us have time for when working ‘normally’.

This is all very well. But when we strike, we lose income because our employers deduct wages. Many university workers simply struggle to afford strike action – hence the need for hardship funds. We desperately need tactics that: 1. Minimise our loss of income; 2. Maximise damage to our employers; 3. Mitigate harm to those we care about. We’ll return to this question at the end.

It’s highly likely we will face some more specific challenges in the coming years, those arising from the particular political climate in the UK, the election in December 2019 of another Conservative government led by Boris Johnson, and the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

Higher education as an export is enormously important to the UK’s economy. Foreign students generate income of £20 billion or more each year. A briefing for a House of Lords debate on ‘the value to the United Kingdom of higher education as an export’ also notes the non-monetary benefits: apparently ‘the UK’s education sector is a major contributor to the UK’s soft power’.[3] In post-Brexit Britain we can only expect universities’ importance as generator of foreign-export earnings to increase. But the global education market is highly competitive and growing ever more so as more Chinese and Indian universities become ‘world class’. Ultimately competition is about which bosses can extract most (surplus) value from their workers, about which bosses can make their workers work hardest, most productively, for the lowest wages. Universities are no exception. An ill-disciplined labour force isn’t good for business. In the midst of the Feb–March 2018 strikes, the Chinese embassy in Britain expressed its concerns to the British government, citing the ‘legitimate right of Chinese students studying in Britain’. (There are over 120,000 Chinese students in Britain – one third of all non-EU students – each pays typically £52,000 in tuition fees over the period of their study.) Threatening this revenue stream clearly makes our industrial action more powerful, but it might also draw an aggressive response by vice-chancellors – with the full support of the government we would predict.

A second broad threat is around the issue of ‘academic freedom’. Briefly, this threat is double. On the one hand, scholars are increasingly constrained by what they can and cannot say. Public criticism of one’s own employer or one of its associates (a sponsor or funder, say) may bring disciplinary charges of bringing the institution into disrepute. (This goes against quite explicit UNESCO recommendations on the matter.) The Prevent agenda also seriously circumscribes academic freedom.[4] On the other hand, as part of a wider conservative attack on universities, seen by Daily Mail–Telegraph–Times types as ‘bastions of left-wing thought’ (if only!), we are likely to see more engineered confrontations over the rights (or ‘rights’) of alt-right scholars such as Jordan Peterson or trans-exclusionary radical feminists to speak on campuses.

Action

short of beyond a strike

We began by recalling the pitiful 2-hour strikes of 2014. But we don’t have any objection in principle to 2-hour stoppages.

Early 2018’s small explosion of militancy also blew open our union. Since its creation in 2006,[5] UCU has been controlled by two opposing factions. The so-called Independent Broad Left is an unholy alliance of Communist party-types and Blairites. UCU Left includes those on the left of the Labour party and some independent socialists, but it is dominated by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). Both factions have benefited from a largely passive and unengaged membership. There was widespread anger in UCU at the way the February–March 2018 strikes were organised – with this anger mostly directed at then-general secretary Sally Hunt and the IBL faction. UCU Left failed to capitalise on this, however. In fact, many younger and newly-militant UCU activists are openly hostile to UCU Left – because of its connection to the SWP, which is now widely reviled.

Sally Hunt resigned as UCU’s general secretary on health grounds in February 2019. For us, a telling incident occurred during one hustings of the three candidates vying to replace her. A question was asked about the effectiveness of strike action – and possible alternatives to strike action. The IBL candidate, Matt Waddup, and that of UCU Left, Jo McNeill, both stressed the primacy of the strike and gave short shrift to the possibility we might explore other forms of action. As part of her answer, McNeill likened the university to a factory. In striking contrast, the third candidate, Jo Grady, made two points, equally important. First, a university is not like a factory, for many reasons. Second, in reality, factory workers, in the car industry for example, deployed many other forms of industrial action in addition to the all-out strike: go-slows, work-to-rules, rolling strikes, including even 2-hour rolling strikes, where workers on different sections of the production line would each strike for a short period in turn.

Car workers, along with many other industrial workers, were able to use such tactics to good effect because they had an intimate knowledge of their workplaces and the labour process. They knew the choke points, the points where their employer was vulnerable and were thus able to exploit this knowledge. Militants working in universities have neglected to do the research and thinking necessary in order to understand our employers’ vulnerabilities. How could we strike against a university’s brand, for instance – so important to the recruitment of fee-paying students and in attracting other income? How could we disrupt a university’s compliance with regulatory bodies such as the Office for Students or the Home Office? As we see it, one of the most important aspects of all-out strikes is their affective power, their ability to engender collective solidarity. But we desperately need other tactics too: forms of action that are more disruptive to our employer at less cost to us, that is, that don’t involve thousands of workers each losing many days’ pay.

As important, we believe, is to develop a more constitutive politics and practice in the university. By this we mean politics and practices that shape the university in such a way that it better suits our needs. There are (at least) two elements to this.

First of all, a university must be a sanctuary of sorts. Academic or intellectual freedom must be defended. But intellectual freedom is dependent on material security. Besides struggles against precarity and student indebtedness, this means undermining the UK’s border regime and the Prevent mechanism in every way possible – which also disrupts the university’s smooth running.

Second, a wide variety of teaching and research takes place in universities. (Some would say this is the very definition of a university.) Some of this scholarship has the potential to serve our needs. But much teaching and research is very much in the interests of capital – and against us. Campus militants should take a stance against university collaborations with the Ministry of Defence, arms companies, oil and gas companies and the like.

Nobody today seriously thinks universities are ivory towers. But we go further and suggest that universities encompass society. In the UK, they employ almost half a million people, just under 1½% of the total number in employment; a further 2.3 million people work in universities as students. The present UCU disputes concern wages, inequality and working conditions of one section of university employees. But universities are riven with class and class conflict – from above, from below and from the side. Class is happening in universities.[6] Almost every major struggle we can think of manifests itself in some way on campuses in Britain. Prevent, the ‘hostile environment’, debt, free speech, the rights and dignity of trans and other gender-diverse people. We have already mentioned or alluded to all of these. There are plenty of other examples.

Our

purpose in writing this is not to tell militants that they should ‘join the

union’ – not UCU nor any other. But we do want militants – especially those who

work in higher education – to pay attention to the richness and diversity of

struggles currently occurring in that sector – some channelled through unions,

but most not. Strikes always have the potential to overflow their formal

demands or ‘claims’. They’re never just about wages or working hours –

whatever trade union leaders and negotiators say or believe. That’s the other

reason they should not be ignored and cannot be dismissed. The UCU strikes at

the beginning of 2018 and at the end of 2019 were no exception. Nor will be the

UCU strikes that begin in just a few days’ time.

[1] Trade union membership is a so-called protected characteristic – like religion or sexuality. This means a boss cannot ask whether any particular employee is a member of the union. So, if a strike is lawful, then any employee, member of the union or not, may legally participate.

[2] This is not quite the whole story. Until the 1980s, unemployment benefits in the UK were, if not generous, sufficient to live on and required little more effort than ‘signing on’ every week or two. Hence a vibrant ‘dole culture’ was possible: thousands of people pursued musical, artistic, intellectual and political projects with the material support of the state. That’s all gone now. But, for a small number of people, PhD scholarships have served a similar function to the dole – offering an income sufficient to grant the individual a relatively free existence for a few years.

[3] The data come from this 2018 report by London Economics for Higher Education Policy Institute and Kaplan International Pathways. The House of Lords briefing is here.

[4] For more on academic freedom see this USS Brief.

[5] A result of a merger between AUT, which mostly represented workers in ‘old’ or ‘pre-92’ universities, and NATFHE, whose members mostly worked in former polytechnics (‘post-92’ universities) and further education colleges.

[6] We’re alluding here to E.P. Thompson’s formulation in his preface to The Making of the English Working Class. Making the argument that we should understand class as a category of struggle (rather than as static sociological pigeon holes), Thompson writes that ‘class happens’.