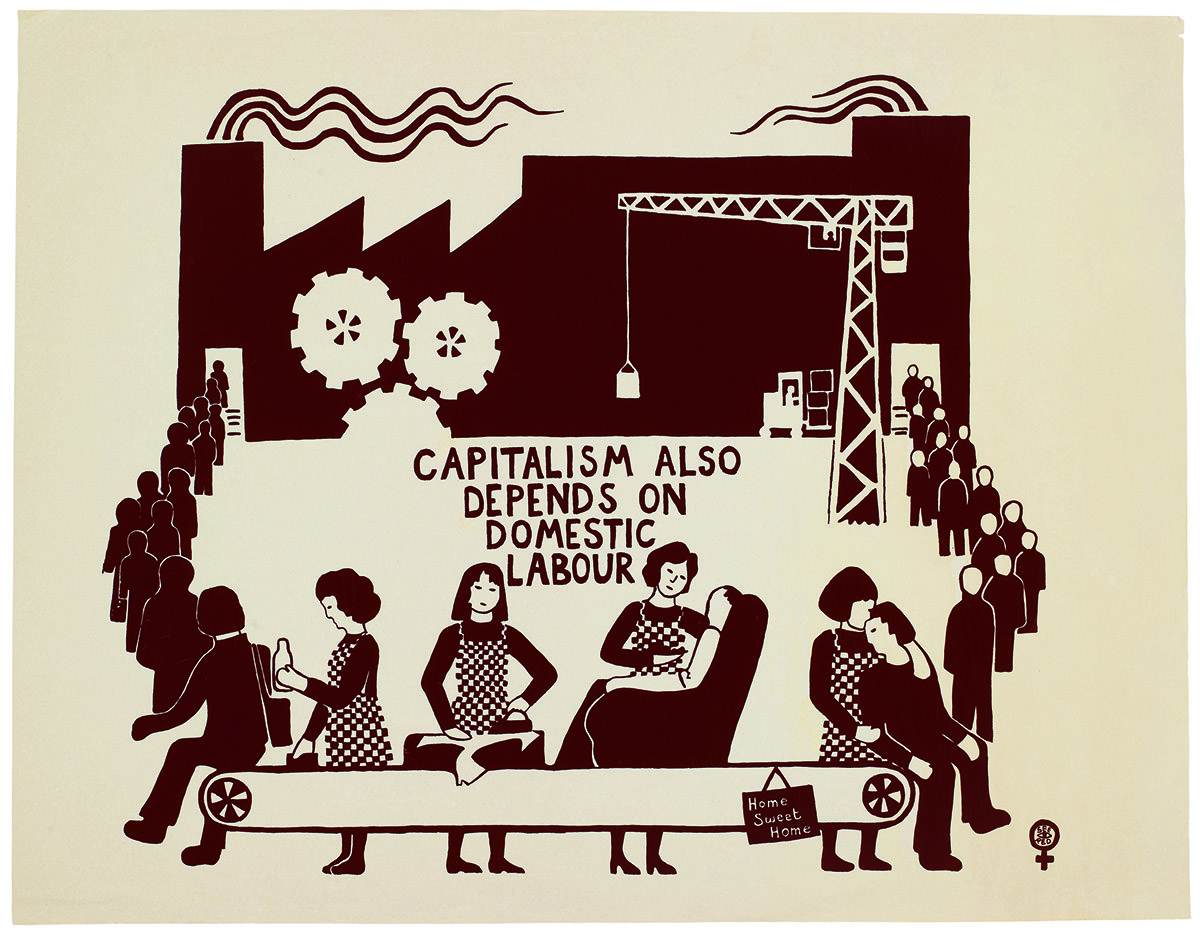

Social reproduction is what keeps us alive; capitalist production is what’s killing us

By Plan C members Susy and Katie

The coronavirus pandemic has led to an intensification of reproductive care work, inside and outside of the home, carried out mostly by working class women, migrants and women of colour. A huge recruitment drive for social care workers is underway, targeting laid-off airline hostesses and hospitality staff. Schools have been made to stay open to care for the children of key workers, ranging from those employed by the NHS, to those working to maintain our utilities and working in food distribution. Previously, 30% of our food and drink expenditure took place outside of the home; now, with the closure of food outlets, not to mention growing food scarcity, there are more mouths to feed for more of the time and this means more cooking.

Most social reproductive work is done by women, as are most of the jobs currently defined as ‘key work’, which means women overall are bearing the brunt of the changing distribution of work during this epidemic. 22 out of 28 key worker occupations have the highest risk factors for coronavirus. Nurses, nursing assistants and auxiliaries face the highest risk; care workers and home carers face a high risk too. In total, 75% of the high risk workforce are women. 98% of those in high risk jobs who are being paid poverty wages are women.

Many women have lost jobs that were never secure in the first place, or been forced to leave or stop work as no childcare is available. This has had a devastating impact on single parents in particular. For those laid-off from precarious jobs, claiming Universal Credit has become a much longer process, with an average of 1.5 hours wait to get on the website to make a claim. With over 4 million people at risk of food insecurity, many mothers would rather go hungry in order to feed their loved ones. Those who can live with partners who have been laid-off, will end up in the high risk occupations outlined above, like nursing and caring, and hence face greater risk to themselves and their families. Clearly, pandemic inequalities have a class, race and gender dimension, as we discuss in a recent article.

In the UK, almost all childcare provision is private, one of the most expensive in the world not matched in quality. Childcare provision has been boosted via marketisation, with the state subsidising providers and giving low-paid parents childcare tax credits. Almost 50% of providers have now shut down, as it is not viable for them to stay open. For key workers with children under school age, this is a major issue, particularly when both parents are key workers or if there is only one parent. 25% of families with children are single parents and mostly women. Single mothers who are NHS or care workers are left in a difficult conundrum. They can continue working and move their children to their ex spouse/partner or grandparents’ home, which inevitably entails not seeing their children for a while, because it wouldn’t be safe. Or they can stop going into work, lose income and stop looking after the ill and vulnerable.

What we want to outline here is that this pandemic has brought to the fore both the primary importance of women’s work through social reproduction to the continuation of the human species and of capital itself, and the crisis of care that feminists and all those involved in struggles for reproductive justice have been talking about for decades.

Despite its increased significance, social reproduction work in the home in particular continues to be undervalued, in sharp contrast to the Government job retention scheme and packages offered to save those who are self-employed or owners of small businesses.

Sex workers have been massively hit by the lock-down measures, yet, without measures to fully decriminalise the industry, huge numbers who are employed precariously in illegal or informal places of work are not able to access any of the government support packages, nor do they have access to other labour rights such as sick pay. Many are supporting children, parents or disabled relatives and already surviving on a pitiful income. Now they face homelessness and starvation.

Whilst thousands of people were clapping for the NHS workers who are having to care for so many at increasing risk to themselves, there was no clapping for the 8 million live-in or visiting home care workers, the 1.6 million social care workers (let alone the billions of women worldwide who do care work unpaid simply by virtue of their role as ‘mother’, ‘daughter’, etc.). The recent recruitment drive for social care workers invited anyone with “good people’s skills” to apply – overlooking the skills and knowledge carers have in order to rationalise low-pay and insecure working conditions. To this we need to add all of those women that have become home carers as a result of COVID-19, not included in these statistics. The government’s 1.5 million food parcels scheme for vulnerable people does not cover those who are cared for by family members. What is more, home carers have received no specific guidance, no Personal Protection Equipment (PPE), and are not being considered for testing.

A crisis under capitalism is a crisis of social reproduction

The corona crisis, like so many crises under capitalism, has shown us that social reproduction is central to our survival. A so-called ‘crisis’ makes this work visible, because under capitalism we are living in a crisis of social reproduction. The work women do in our homes and our neighbourhoods, in care homes, in hospitals, schools and charities – the work that is fighting the coronavirus and keeping us alive – is the work that keeps the capitalist world order in motion. It is no surprise to us that a further disruption in the already invisibilised realm of social reproduction work has far reaching economic consequences, not to mention those for our health, survival and well-being. Even in the context of everyday struggles around employment, in which all adults irrespective of their caring responsibilities are expected to be in some form of paid work, the site of resistance and connections has shifted to our homes, gardens, balconies, physical and virtual neighbourhoods, care homes, hospitals, schools and community projects.

This has long been the site of struggle for feminist movements such as the Women’s Strike. Just a couple of weeks before the “lockdown” was declared in the UK, millions of women worldwide took to the streets on 8 March to celebrate and imagine a future in which all our work, paid and unpaid, is valued and shared. Thousands more withdrew their labour on 9 March and joined in solidarity with the UCU strikes in universities and colleges around the country. Among us that weekend were sex workers on strike against the sexist and racist criminal laws that put their lives at risk and alongside us were our sisters and comrades from Latin America and Kurdistan who have been resisting patriarchy in its most organised and institutionalised form – state fascism – as the driving force behind all violence against women. Unfortunately, patriarchal violence does not rest, nor will it be quarantined. Neither, therefore, must we. It is we who are the agents behind the care and maintenance of society and life as a whole. And it is we, the feminist movement, who have the capacity to mobilise and organise society from below.

A feminist response to the crisis

We have seen a lot of concern in the news about irresponsible hoarding behaviour and the refusal to comply with social distancing. This of course was the justification the government was looking for to introduce the Coronavirus Bill and increase its powers. In reality, as we have shown in a recent article, the true irresponsible people have been the government, and the CBI who put pressure on the government to delay pandemic control measures. Even amongst left circles there have been concerns that individualisation would hamper collective resistance and solidarity.

Yet, if we look at the response to the crisis with a feminist lens we see a very different picture. Individualisation is rife and it is institutionalised. For example, the cause of poverty is now often seen in the failure of individuals to adapt to social changes, which requires a punitive welfare state (sic). But individualisation is also about what Ulrich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim describe as “the compulsion to lead a life of one’s own and the possibility of doing so”: a struggle for autonomy and freedom from the social ties and roles that have been ascribed to us on the basis of natural essentialism.

The corona crisis is showing us that we are not selfish, detached and irresponsible. What we see are hundreds of thousands of mutual aid groups springing up all over the country and over 2.5 million people volunteering. Physically isolated from one another, craving to be with others, we have developed thousands of creative ways to get together online, or by singing, partying and playing music across our balconies and gardens.

Many would say this is a typical response to a crisis. But we think there is a lot more to it. What we see is that we are striving for a related autonomy, one which can only be achieved in connections and mutual care with others. Related autonomy is developed through practices of solidarity and balanced mutual care. It is this that enables us to be powerful and fight the corona crisis and institutionalised individualism.

The pandemic has exacerbated inequalities and shown us clearly that poverty and illness are not the result of individual failure. Covid-19 is affecting all of us, Covid-19 could kill all of us. Yet people are experiencing this risk differently. For example, whilst smart workers on secure contracts are able to work from home and rely on their normal income, many key essential workers are having to work in unsafe conditions, doing overtime and working nights without any pay security or PPE. Thousands of workers on zero hour contracts have been laid off, and now face hunger and evictions. Sex workers have lost their income overnight, most with no protection. The majority of these workers are women.

In furthering the crisis of capitalism, coronavirus has shown us that change is possible. Change has happened. We understand now more than ever that we all need care and that care cannot be left to low or unpaid working class women, migrants and women of colour. Nor can it be fully commodified, outsourced or carried out online. When we are in need of care, we often need to be washed, spoon-fed, touched. Even when we do not need physical care we want the presence and touch of others, as well as those benefits afforded to us by technology.

Having come closer to our mortality, we are not content to fight for ‘herd immunity’, despite the government’s ludicrous claims that this was the only way out of this crisis. We need a paradigm shift. We need a revolution in care. We need each other.

Social reproduction is what is keeping us alive. Capitalist production is what is killing us. We can support each other; together we are strong. As Arundhati Roy has written, “Another world is possible. She is on her way. On this quiet day I hear her breathing.”