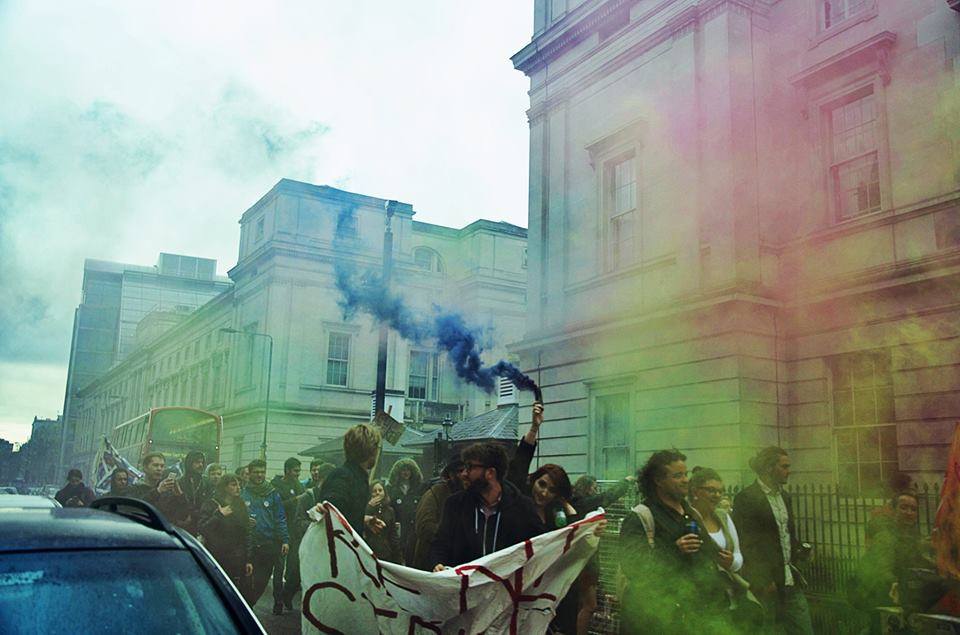

The recent UCL rent strike was a landmark event in UK student politics. 1000 students in halls refused to pay up, and won £850,000 in concessions from their university. Brighton Plan C invited some of the rent strikers down to Brighton to talk about their successes, the connections between the rent strike to the social strike, and the potential for more rent strikes in universities over the coming year.

The interview took place on the beach, sheltering from the wind under a #RentStrike banner. Callum Cant (CC) and Bill Whitney (BW) were asking the questions, Ben Beach (BB), Angus O’Brien (AOB) and Iida Käyhkö (IK) were answering them.

CC: What are the differences between a rent strike and a classical work strike? At UCL you’ve had experience with different types of classical strikes, from UCU to the 3 Cosas, do you have any reflections on the differences between them and the rent strike?

BB: A rent strike kind of is a strike in the direct production process, and that’s something that’s quite important now due to fundamental changes in the character of rent and housing. They’re now part of a valorisation circuit. Specifically within the university, rent and housing makes a huge contribution to their finances in the context of budget cuts, so now they’re literally leveraging the estate to make up for big cuts in funding.

Across the city – the city itself has become a debt factory, and it’s main purpose is to circulate financial products and create the conditions for a securitised land market. The city has become a manufacturing centre for debt. There is actually a direct production process happening here in a way that wasn’t perhaps qualitatively true four decades ago.

CC: So social reproduction and direct production have come together?

BB: Yeah I’d go with that. You love a bit of Negri and Tronti and all that – well, society is a factory. We’re all in the social factory now, especially in post-industrial service economies, like Britain. There are loads of incidences of social reproduction now directly producing that value. So a rent strike is coming closer to a direct strike you’d see in a factory, like Ford workers in a car factory.

And this comes back round to the whole social strike thing. No one seems to really be able to say what the social strike is, beyond: ‘it’s a strike and its kind of social’. Don’t get me wrong, I’m down with it, but at the moment its just a bit of a holding pattern. It needs some definition. If you’ve lost the ability to do full on strikes because all the trade unions have been hammered and you’ve seen a move away from industrial workplaces that enable this mode of action, these forces are being recomposed somewhere else, and rent is one area where you could cause a lot of disruption to the social factory. We’re losing a mode of action, but we’re gaining another. We need to reconfigure the terrain that strikes are taking place in – and that, if anything, is the social strike.

AOB: In terms of actually organising, a rent strike is much easier than a classical strike – because all you have to do in order to join the strike is… nothing. The first step in what is quite a radical action – withholding rent, going up against eviction and so on – is to not take five minutes to pay your rent. That’s something we completely underestimated. We’d go round telling people how easy it was, and the message really got through, and we got to this point where people were really doing it. We didn’t realise how willing people would be to do it. They withheld their rent and that was it. We had 1000 rent strikers because of how easy it was to go on strike.

One other dynamic was that a rent strike causes a collection problem rather than a production problem: the university can always come after the money you’re withholding, whereas with a work strike every second you aren’t working, they’ve lost that money forever.

IK: I’d say one of the big differences was that in a traditional strike you’d have a union organising it who know what they’re doing, and everyone taking part understands that its a radical action. We were lacking that. A lot of strikers didn’t get the politics behind it.

BB: We had to push to get people to understand the politics. Rent is a political thing. We were trying to find a balance that allowed for soft-p politics. People would be like ‘I don’t want to get too political about it’, like, you’re on rent strike, you’re already being fucking political about it! You need to be more political, not less, if you want to win it. It’s not about just not liking the rent.

CC: So people need to understand that rent is a political relationship not just an inconvenience?

BB: Yes, exactly.

AOB: We were so worried about it not happening that we tried to make softer, but now the actual idea has been proven we don’t need to be so anti-political again. It was a mistake to do it in the first place.

BW: What were the political motivations of the people on rent strike?

IK: Towards the end of the strike there was a weird splintering of strikers. First we got some people who were annoyed that they wouldn’t get any money back, and that there would only be a rent cut for next year. These tended to be the people who just wanted to pay less. But then once we got the offer from the university there was another group who wanted to carry on with the strike.

We expected the first, but not the second. These suddenly ultra-radical strikers, who wanted to strike through summer and push for more – they came out of nowhere.

CC: How big was that second group?

IK: We had a ballot online over the offer, and I think about 30% of those that voted said they didn’t want to accept it. Bearing in mind we’d released a thing from the negotiation team advising people to accept the offer because we didn’t have the resources to go into a strike over the summer, and that it could end badly. If we hadn’t done that, they might not have accepted the offer at all.

CC: Today a huge majority of students work, a majority suffer from symptoms of mental illness, most are in 40k of debt… you’d be justified, I think in claiming that there’s a crisis of social reproduction amongst students, and that it’s a major factor in limiting political action. How does the rent strike relate to this crisis?

IK: I’ve had a lot of thoughts about this recently, because I’ve been looking into Assata Shakur and revisiting Audrey Lorde who I first read a few years back, and thinking about the role of self care and solidarity in activist movements. I feel like actually that was something that we could have done a lot better, should have done better, in fact.

In general it would have been better to have more granular organisation in halls and have a genuinely participative and democratic structure. We didn’t manage to create that in the way we wanted to. But it would have been very beneficial to give people a sense of control and security. If you’re 18, at uni in London, working part time, and studying, and taking part in a rent strike, and then you aren’t sure what’s happening and your parents are putting you under pressure and you have issues with anxiety as a result… thats a lot to be dealing with. There were probably a lot of people in that situation, and personally I think we should have taken better care of them. Universities are very alienating environments in general. They leave you alone, they offer very little support in terms of mental health, and it would be really cool to also make the rent strike act as a support system that always has people you can talk to and who can explain what’s going on. I’m not saying we made everyone feel like trash, but I’d be really interested in improving this aspect in the future.

You can’t put on a rent strike without building the kind of movement that could resist universities trying to evict students. If they come for us, we need to be able to defend ourselves.It’s not just about trying to disrupt the university, it’s also about liberating ourselves to live as we want to live inside the university. If you can do that, then you can start to actually build power. Campuses in Chile, Greece, Mexico, Spain etc. are concrete sources of power for social movements because they’re places where a different kind of social, communal life goes on.

I feel like the student mental health crisis has been ignored, and its impact on potentials for mobilisation have been forgotten. But it’s clearly the reason that we’re largely unable to act, because people are too depressed or too anxious to struggle. It’s the major reason why 2010 hasn’t repeated itself.

CC: Last year there were attempts to move towards a student strike in the UK, which were pretty dismally unsuccessful, whereas the rent strike has been a real step forward for student politics. Given the logics of the two actions are similar, why do you think one succeeded where the other failed?

BB: Well, some of us told you this earlier [laughter]. Something I was thinking about the social care thing – with a rent strike you’re addressing an immediate material concern, and if you win the consequences are an immediate release of pressure from your life. Conversations about self-care and social reproduction as a student lead towards this point, where you develop a tangible material intervention to grapple with the problem in the form of a rent strike.

Whereas, there isn’t really a conversation about fees any more. NCAFC has been in the doldrums for a long time, and there isn’t a national anti-fees movement despite there being a lot of people who are anti-fee. And a student strike relies on a series of abstractions.

How do you justify a students strike as a strike, and make the case for leveraging economic power? A work strike has economic power in the workplace, a rent strike has economic power in the city, a student strike has what power where? The cost of entry to higher education is so high that you’re not going to let it go to waste. It’s a hard sell. Students are putting themselves in a position at great personal expense, they’re not going to ignore it’s benefits.

I think a rent strike is very real, and in front of you, and a student strike is an abstraction. The tactic is as abstraction, the target is an abstraction, the issue is an abstraction – and you have to make a political argument that can get you between all three. Whereas with rent, all we had to say was: you’re paying too much, stop paying for a bit and we’ll try and cut it. It was really obvious. For me, thats the difference.

CC: How realistic is it to hope that the rent strike tactic will generalise the rent strike amongst students?

AOB: It’s very realistic, watch and see. [laughter]

A Rent Strike Weekender has been organised to bring together people from across the student movement to explore the potential for spreading the rent strike on the 16th-18th of September.